Industrialized Consciousness

(1) The Railroad Journey - Projectile Traveling (or, Bullet Trains of Yesteryear)

"A train moving at 75 miles per hour "would have a velocity only four times less than a cannon ball."

– D. Lardner, Railway Economy (1850)

The Flight of Intellect; Portrait of Mr. Golightly, experimenting on Mess Quick & Speed's new patent high pressure Steam Riding Rocket

– anonymous, ca. 1830

The railway "transmutes a man from a traveller into a living parcel."

– John Ruskin

"Impression et Compressions de Voyage," Les Chemins de Fer

– Honoré Daumier, Le Charivari, 25 July 1843

(2) The Rhetoric of the Technological Sublime

The popular phrase: "the annihilation of space and time"

– Alexander Pope

Motions and Means on land and sea at war

With old poetic feeling, not for this,

Shall ye, by Poets even, be judged amiss!

Nor shall your presence, howsoe'er it mar

The loveliness of Nature, prove a bar

To the Mind's gaining that prophetic sense

Of future change, that point of vision, whence

May be discovered what in soul ye are.

In spite of all that beauty may disown

In your harsh features. Nature does embrace

Her lawful offspring in Man's art; and Time,

Pleased with your triumphs o'er his brother Space,

Accepts from your bold hands the proffered crown

Of hope, and smiles on you with cheer sublime.

– William Wordsworth, "Steamboats, Viaducts, and Railways" / Wordsworth's more negative response

We believe that the steam engine, upon land, is to be one of the most valuable agents of the present age, because it is swifter than the greyhound, and powerful as a thousand horses; because it has no passion and no motives; because it is guided by its directors; because it runs and never tires; because it may be applied to so many uses, and expanded to any strength.

– anonymous author in a business magazine, 1840

Here is one, for instance, lying at the base of all the rest---namely, what may be the real dignity of mechanical Art itself? I cannot express the amazed awe, the crushed humility, with which I sometimes watch a locomotive take its breath at a railway station, and think what work there is in its bars and wheels, and what manner of men they must be who dig brown iron-stone out of the ground, and forge it into THAT! What assemblage of accurate and mighty faculties in them; more than fleshly power over melting crag and coiling fire, fettered, and finessed at least into the precision of watchmaking; Titanian hammer-strokes beating, out of lava, these glittering cylinders and timely-respondent valves, and fine ribbed rods, which touch each other as a serpent writhes, in noiseless gliding, and omnipotence of grasp; infinitely complex anatomy of active steel, compared with which the skeleton of a living creature would seem, to a careless observer, clumsy and vile---a mere morbid secretion and phosphatous prop of flesh! What would the men who thought out this---who beat it out, who touched it into its polished calm of power, who set it to its appointed task, and triumphantly saw it fulfil this task to the utmost of their will---feel or think about this weak hand of mine, timidly leading a little stain of water-colour, which I cannot manage, into an imperfect shadow of something else---mere failure in every motion, and endless disappointment; what, I repeat, would these Iron-dominant Genii think of me? and what ought I to think of them?

– John Ruskin, "The Tenth Muse," The Cestus of Aglaia, first printed in Art Journal, February 1865

(3) The New Sense of Speed and Sight

Left Frankfurt shortly after 7:00 A.M. On the Sachsenhausen mountain, many well-kept vineyards; foggy, cloudy, pleasant weather. The highway pavement has been improved with limestone. Woods in back of the watch-tower. A man climbing up the great tall beech trees with a rope and iron cleats on his shoes. What a village! A deadfall by the road, from the hills by Langen. Sprendlingen. Basalt in the pavement and on the highway up to Langen; the surface must break very often on this plateau, as near Frankfurt. Sandy, fertile, flat land; a lot of agriculture, but meagre. . . .

– Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, journal on his trip to Switzerland, 1797

Lady Wilton sent over yesterday from Knowsley to say that the locomotive machine was to be upon the railway at 12 o'clock. I had the satisfaction, for I can't call it pleasure, of taking a trip of five miles on it, which we did in just a quarter of an hour---that is twenty miles an hour. The machine was really flying, and it is impossible to divest yourself of the notion of instant death to all upon the least accident happening. It gave me a headache which has not left me yet.

– Thomas Creevey, MP, Nov. 1828

She (for they make these curious little fire-horses all mares) consisted of a boiler, a stove, a small platform, a bench, and behind the bench a barrel containing enough water to prevent her being thirsty for fifteen miles . . . . You can't imagine how strange it seemed to be journeying on thus, without any visible cause of progress other than the magical machine, with its flying white breath and rhythmical unvarying pace, between these rocky walls, which are already clothed with moss and ferns and grasses; and when I reflected that these great masses of stone had been cut asunder to allow our passage thus far below the surface of the earth, I felt as if no fairy tale was ever half so wonderful as what I saw. . . . You cannot conceive what that sensation of cutting the air was; the motion is as smooth as possible, too. I could either have read or written. . . . When I closed my eyes this sensation of flying was quite delightful, and strange beyond description; yet, strange as it was, I had a perfect sense of security, and not the slightest fear . . . [as] this little brave she-dragon of ours flew on. (26 August 1830)

– Fanny Kemble, Record of a Childhood, 1878

The flowers of the side by the road are no longer flowers, but flecks, or rather streaks, of red or white; there are no longer any points, everything becomes a streak; the grainfields are great shocks of yellow hair; fields of alfalfa, long green tresses; the towns, the steeples, and the trees perform a crazy mingling dance on the horizon; from time to time, a shadow, a shape, a spectre appears and disappears with lightning speed behind a window: it's a railway guard.

– Victor Hugo, view from train window, August 1837

The power that forced itself upon its iron way - its own - defiant of all paths and walls, piercing through the heart of every obstacle, and dragging living creatures of all classes, ages, and degrees behind it, was a type of the triumphant monster, Death. Away, with a shriek, and roar, and a rattle, from the town, burrowing among the dwellings of men and making the streets hum, flashing out into the meadows for a moment, mining it through the damp earth, booming on in darkness and heavy air, bursting out again into the sun so bright and wide; away, with a shriek, and a roar, and a rattle, through the fields, through the woods, through the corn, through the hay, through the chalk, through the mould, through the clay, through the rock, among objects close at hand and almost within grasp, ever flying from the traveller, and a deceitful distance ever moving slowly within him: like as in the track of the remorseless monster, Death! . . . . Breasting the wind and light, the shadow and sunshine, away, and still away, it rolls and roars, fierce and rapid, smooth and certain, and great works and massive bridges crossing up above, fall like a beam of shadow an inch broad, upon the eye, and then are lost. Away, and still away, onward and onward ever: glimpses of cottage-homes, of houses, mansions, rich estates, of husbandry and handicraft, of people on old roads and paths that look deserted, small, and insignificant as they are left behind: and so they do, and what else is there but such glimpses, in the track of the indomitable monster, Death! Away, with a shriek, and a roar, and a rattle, plunging down into the earth again, and working on in such a storm of energy and perseverance, that amidst the darkness and whirlwind the motion seems reversed, and to tend furiously backward, until a ray of light upon the wet wall shows its surface flying past like a fierce stream. Away once more into the day, and through the day, with a shrill yell of exultation, roaring, rattling, tearing on, spurning everything with its dark breath, sometimes pausing for a minute where a crowd of faces are, that in a minute are not.

– Charles Dickens, Dombey and Son, 1847

[Passengers] arrive at their destination overwhelmed by a previously unknown fatigue. Just ask these victims of velocity to tell you about the locations they have traveled through, to describe the perspectives whose rapid images have imprinted themselves, one after another, on the mirror of their brain. They will not be able to answer you. The agitated mind has called sleep to its rescue, to put an end to is overexcitation.

– Gustave Claudin, Paris (1867)

The passenger by this new line of route having to traverse the deepest recesses where the natural surface of the ground is the highest, and being mounted on the loftiest ridges and highest embankments, riding above the tops of the trees, and overlooking the surrounding country, where the natural surface of the ground is the lowest - this peculiarity and this variety being occasioned by that essential requisite of a well-constructed Railway - a level line - imposing the necessity of cutting through the high lands and embanking across the low; thus in effect presenting to the traveller all the variety of mountains and ravine in pleasing succession, whilst in reality he is moving almost on a level plane and while the natural face of the country scarcely exhibits even those slight undulations which are necessary to relieve it from tameness and insipidity.

– Henry Booth, An Account of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, 1830

(4) The Panorama: Perceiving the Discrete Indiscriminately

Devouring distance at the rate of fifteen leagues an hour, the steam engine, that powerful stage manager, throws the switches, changes the decor, and shifts the points of view every moment; in quick succession it presents the astonished traveler with happy scenes, sad scenes, burlesque interludes, brilliant fireworks, all visions that disappear as soon as they are seen; it sets in motion nature clad in all its light and dark costumes, showing us skeletons and lovers, clouds and rays of light, happy vistas and sombre views, nuptials, baptisms, and cemeteries.

– Benjamin Gastineau, La vie en chemin de fer (1861)

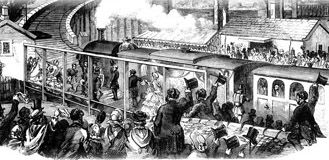

The engines proceeded at a moderate speed towards Wavertree-lane, when increased power having been added, they went forward with great swiftness, and thousands fell back, whom all the previous efforts of a formidable police could not move from the road. Numerous booths and vehicles lined the various roads, and were densely crowded. After passing Wavertree-lane, the procession entered the deep ravine at Olive Mount, and the eye of the passenger could scarcely find time to rest on the multitudes that lined the roads, or admire the various bridges thrown across this great monument of human labor.

– "Opening of the Railway," 15 September 1830, Mechanics Magazine

I cross the Laramie plains, I note the rocks in grotesque shapes, the buttes,

I see the plentiful larkspur and wild onions, the barren, colorless, sage deserts,

I see in glimpses afar or towering immediately above me the great mountains, I see the Wind river and Wahsatch mountains,

I see the Monument mountain and the Eagle's Nest, I pass the Promontory, I ascend the Nevadas,

I scan the noble Elk mountain and wind round its base . . . .

– Walt Whitman, "Passage to India" (1871)

(5) Reading: From Outer Landscape to The Landscape of Books

Dreamlike traveling on the railroad. The towns which I pass between Philadelphia and New York make no distinct impression. They are like pictures on the wall. The more that you can read all the way in a car a French novel.

– Ralph Waldo Emerson, Journals, 7 February 1843

Interior of a First-Class Carriage – Honoré Daumier, 1860s

Nowadays one travels so fast and sees, if the journey is of any duration, such a succession of new faces, that one frequently arrives at the destination without having said a single word. Conversation no longer takes place except among people who know each other at least not beyond the exchange of mere generalities. . . . Thus one might say that the railroads have, in this respect, too, completely changed our habits. . . . . Today we no longer think about anything but the impatiently awaited and soon reached destination. The traveler one takes one's leave from may get off at the next station where he will be replaced by another. Thus reading becomes a necessity.

– French Medical Congress, 1860

A Third-Class Carriage – Honoré Daumier, 1860s

The Travelling Companions – Augustus Leopold Egg, 1862