Japanese American Educator, Inclusion Advocate Honored in ‘Women of Weber’ Exhibit

OGDEN, Utah – Equity, diversity, inclusion: These three words have seeped deeply into the country’s collective consciousness recently, but for Weber State University Professor Emeritus of Education Linda Oda, the principles behind these words have guided her through life. Over the course of more than five decades, she’s worked in Utah as a teacher, principal, professor, administrator, governor’s director of Asian Affairs and, now, as a volunteer for Weber State programs that support diversity.

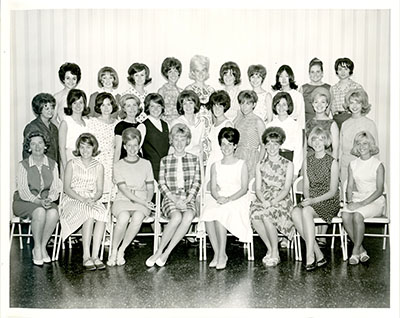

This month, Weber State University is honoring Oda as part of the “Women of Weber” project, which focuses on extraordinary women whose service, accomplishments, careers and philanthropy have enriched lives and educational experiences at the university. Each month throughout the academic year, one woman’s photos and stories will be on display outside Archives on the first floor of the Stewart Library.

.jpg) The project was an outgrowth of a collaboration with Weber State Archives, Special Collections and the Museums at Union Station called “Beyond Suffrage: A Century of Northern Utah Women Making History.” The project was a commemoration of the 100th anniversary of women’s right to vote in 2020. Although the pandemic put a hold on the celebration, it did not dampen the enthusiasm to share the stories of outstanding women who changed lives.

The project was an outgrowth of a collaboration with Weber State Archives, Special Collections and the Museums at Union Station called “Beyond Suffrage: A Century of Northern Utah Women Making History.” The project was a commemoration of the 100th anniversary of women’s right to vote in 2020. Although the pandemic put a hold on the celebration, it did not dampen the enthusiasm to share the stories of outstanding women who changed lives.

Flight to Utah

Linda Oda’s family made a life in Utah not by choice, but out of necessity after fleeing California during World War II when Japanese Americans were forced into internment camps. Oda’s father, Kunimatsu Kay Inouye, and her uncle received word that authorities were looking for them, so they loaded their families and all the possessions that would fit in two cars and overnight left Los Angeles behind, including a prosperous five-story apartment building Oda’s father owned and managed.

They had heard about a friendly farmer who welcomed Japanese families in Perry, Utah, so that’s where they headed.

Inouye worked in the cannery, but an entrepreneur by temperament and training, he and his wife, Norma Hatsue Inouye, soon started buying fresh fish in Salt Lake and selling it in Perry. The success led the family to Ogden, where her dad opened Kay’s Market, a grocery store at 214 25th Street, the building now occupied by Needlepoint Joint. They lived in a home behind the store.

It was an interesting, multi-ethnic, multi-experience childhood. Oda spoke Japanese exclusively until she entered kindergarten. The whole family worked in the store, which stocked specialty foods for a wide clientele.

“The Japanese community ended up there because that was the only place that we were allowed to live,” Oda remembered during an oral history interview with Weber State Archives. “We lived amongst the Chinese and also the African Americans and Hispanics; we were all together, you know.”

When customers arrived with no money, she remembers, her mom gave them bags with lunch meat and crackers.

“There’s a phrase in Japanese ‘‘okagesama de,’’ meaning everything, every good luck, every good fortune always comes from the other person,” Oda explained. “If you believe that your good fortune is always based on somebody else, then obviously, you would always think about the other person, right?”

Although there was little to go around, Oda enjoyed a feeling of community and camaraderie on 25th Street — a street which both welcomed and then devastated her family.

Life on 25th Street offered plenty of diversions. Local kids explored the underground tunnels that led to speakeasies, gambling halls and rooms for clandestine meetings between consenting adults. Oda remembers peeking in the window of an opium den to see men passed out on the floor.

Tragedy on 25th Street

But the most indelible memory Oda has was saying goodbye to her dad at the store on a snowy November morning in 1961 before jumping on the bus to Ogden High School. Soon after arriving, she knew something was terribly wrong when she received a call to catch a cab and come home. For the $100 cash in the register, her dad had been severely beaten during a robbery. He died later that day, and police never caught his killer.

Her family managed to keep the store open as Oda navigated high school and then earned a bachelor’s degree in 1967 in elementary education at Weber State with minors in child development and English. Her educational journey wasn’t easy. She had to balance the little time she had to study, with work and caring for her mother, who, a few years after her husband’s murder, had suffered an incapacitating stroke. For Oda, extra-curricular activities were not an option, but neither was quitting.

Early Days of Teaching

After graduation, she accepted a position as a second grade teacher at Grant Elementary about five blocks from the family store.

After graduation, she accepted a position as a second grade teacher at Grant Elementary about five blocks from the family store.

“In the morning, I’d wake up and let the fresh food people come in and replenish whatever was ordered like vegetables, and then also the milk people,” she recalled. “Then I’d close the store, go to Grant School and teach. And then, Mr. Martin — I’ll never forget Mr. Paul Martin — he was my principal, and he allowed me to leave when the children left. So, as the children were leaving, I left, came back and opened the store temporarily. Then, at six o’clock, I went to the hospital and fed my mom and then came back to the store and opened up until nine o’clock.”

The grueling schedule and the heavy responsibility made her tough, but also deepened her resolve to make the path easier for others, particularly young women of color. Where Oda had found few, if any, female role models in her educational pursuits, she determined to be that person for her students and colleagues.

Transition to Administration

Standing 5-feet tall, Oda developed a big reputation for accepting difficult challenges, not backing down and working to find common ground. After five years as an elementary school teacher, Oda accepted a position as a reading specialist and traveled to schools in Granite, Salt Lake and Weber County school districts for 10 years. She well remembers the day an angry junior high student, who didn’t want to read, punched her in the chest, leaving a deep purple bruise, and the time a male colleague thought it would be funny to lift her off the ground in her dress and heels without warning or consent. Although distressing, she diffused both situations with some quick and effective behavioral course correction.

That same combination of self-preservation, confidence and communication ability benefited her as principal at C.H. Taylor Elementary in Ogden in the mid ’80s. She recalls the school was in “some turmoil” when she took over.

“Teachers would come to me and cry and tell me how difficult it was for them, and parents would bombard me, and we’d have meeting after meeting, and they would cry. And I’d have to say, ‘Okay, this is what we’re going to do,’” Oda said.

Eventually, she “settled things down,” and opened up communication between teachers and parents. While she was working to “settle things down” between teachers and parents at the school, she was continuing her own professional development, earning a doctorate of education in curriculum and instruction at Brigham Young University. During that time, her personal life changed as well. She welcomed the birth of her daughter Libby Tomiko and son Greg Inouye.

“It was hard to go to school, being a principal and having children,” she reflected. “I’ll never forget feeling rather lonely downstairs all by myself after the kids were sleeping, trying to do my studies as well as being a principal, as well as doing my dissertation. It was really a lonely life for a while.”

But her success and professional accomplishments were so obvious, she was selected as curriculum director of the Ogden School District. She was entrusted with both quality and equality. She remembers rejecting a coach’s proposal to offer a summer sports program that excluded female participants.

But her success and professional accomplishments were so obvious, she was selected as curriculum director of the Ogden School District. She was entrusted with both quality and equality. She remembers rejecting a coach’s proposal to offer a summer sports program that excluded female participants.

“‘We’ll have to change that,’ I said. And the coach said, ‘No, we’re not going to change it.’ And, I said, ‘Well, then I’m not signing off on the funding, because it is against the principles of what Ogden School District stands for.’”

Standing up for principles wasn’t always easy, but she grew in confidence and leadership with each assignment. Once her doctoral dissertation was completed, in 1989, she joined the education faculty at Weber State.

Among many accomplishments, her professional highlight during 14 years at the university was the Hemingway Program, which involved a team of six professors: three from education and three from English. Together they developed a systematic and structured approach to mentoring student teachers entering the profession.

“We went on-site to the students, instead of them coming to us,” Oda explained. “We went to their schools and worked with them. For 10 years, we nurtured some excellent leaders who continue to do amazing work in the schools, all the way from high school to elementary.”

Because of the breadth and depth of her experience, Davis School District lured Oda away from Weber State to oversee its Quality Teaching program with a budget of nearly $12 million. At the same time, she was approached to direct the Japanese American National Museum’s Utah Partnership History Project. She and colleague Shanna Futral helped develop curriculum and activities to educate school children and the community about the internment experience, particularly at the Topaz Camp in Delta, Utah, where 10,000 people were forced to survive for three years. Their work eventually led to the construction of the Topaz museum and to the collection and preservation of the stories that bring the museum exhibits to life.

State Director Asian Affairs

In 2007, she began another career, this time with the state. Utah Gov. Jon Huntsman appointed Oda as director of Asian Affairs in the Governor’s Office of Ethnic Diversity, which led to the position as coordinator for the English Language Learner Program at the Utah State Board of Education.

“One of the things that I feel proud about is that the Asian community could come to me,” she said. “On one occasion, a Chinese immigrant called me up and he said, ‘I won’t tell you my name, I won’t tell you anything about me, but there’s a Chinese grocery store owner who is abusing the immigrants, and he’s holding immigration over their heads. They’re working long hours and getting injured on the job.’”

Oda was able to earn the informant’s trust and provide help through the Labor Commission. She loved changing the lives of individuals. While serving in the role, she also had the opportunity to work with former Weber State colleagues on larger initiatives. She supported Professor Emeritus of Education Forrest Crawford in a long but successful effort to get Utah to officially recognize Martin Luther King, Jr. Day. She also solicited the help of former Weber State president and current Utah Sen. Ann Millner, who was then a campus administrator. Millner facilitated the beginning of a successful year-long, statewide conversation with African American, Hispanic, Latino, Native American, Asian American and Pacific Islander parents to improve the curriculum and the treatment of their children at public schools and universities in the state.

Oda was able to earn the informant’s trust and provide help through the Labor Commission. She loved changing the lives of individuals. While serving in the role, she also had the opportunity to work with former Weber State colleagues on larger initiatives. She supported Professor Emeritus of Education Forrest Crawford in a long but successful effort to get Utah to officially recognize Martin Luther King, Jr. Day. She also solicited the help of former Weber State president and current Utah Sen. Ann Millner, who was then a campus administrator. Millner facilitated the beginning of a successful year-long, statewide conversation with African American, Hispanic, Latino, Native American, Asian American and Pacific Islander parents to improve the curriculum and the treatment of their children at public schools and universities in the state.

“People can tell you some incident that’s happened, and you’ll say, ‘That’s not discrimination.’ But if you take 100 of those incidents that happens every day, then at least one of those 100 has to be discrimination,” she said. “Time and time again that’s what happened to Japanese Americans. It happened to African Americans, Hispanic Americans, Native Americans. We all felt that.”

Weber State Volunteer Service Continues

Although some incidents of discrimination are hard to prove, others are codified. Now retired, Oda is helping Jennifer Gnagey, a WSU economics instructor, as she traces the legacy of housing discrimination in Ogden by researching housing covenants that specifically prohibited minorities from owning property in certain neighborhoods.

“Dr. Oda’s lived experiences and insights have been very helpful for this project, and with her background as an educator, she has even offered to help develop curriculum on this topic,” Gnagey said. “It’s so awesome that she’s doing this in her retirement!”

Oda has received accolades for her lifetime of work and service, including the Spirit of American Women Award from the YCC, and WSU’s George and Beth Lowe Innovative Teaching Award. She was elected the first female president of Phi Delta Kappa in northern Utah, a professional organization for educators.

But Oda insists, her main success is perseverance. She just kept going, even when it was hard.

“I may not have been a star, but I just did my best,” she said. “I just had to prove myself every single stretch of the way.”

That’s the message she continues to share as the volunteer advisor for the Peer Mentor Program in the WSU's Office of Access & Diversity, where she helps students learn how to support each other in their academic success. She tells students, both through her words and through the example of a lifetime, that education is not always easy, but worth the price.

“I hope I did something to make the path easier for them,” she said. “I just keep telling them, persist. Continue on. If somebody offers you a credential, go for it, do it. Get your doctorate; get your master’s degree; get your bachelor’s, whatever it is, but get it because they can’t ever take that away from you.”

For photos visit this link.

Visit weber.edu/wsutoday for more news about Weber State University.

Allison Barlow Hess, Public Relations director

801-626-7948 • ahess@weber.edu- Contact:

Allison Barlow Hess, Public Relations director

801-626-7948 • ahess@weber.edu