East-side Stories: Stewart Stadium in the Early Years

Karin Hurst AS ’79, Marketing & Communications

Wildcat family, friends and football fans received a double jolt of purple pride the evening of Sept. 23, 2023. Not only did Weber State kick off Big Sky Conference play with a top-10 national FCS showdown against longtime rival Montana State, but the university also celebrated the opening of the recently renovated Stewart Stadium.

In construction that began in January 2023, the east-side stands were demolished, rebuilt and split into two levels with a walkway and concession concourse. Previously updated in 2011, the playing field now features variegated strips of green turf, an enhanced Wildcat logo and vibrant purple end zones.

The new east-side seating updates one of the oldest structures on the Ogden campus. While the changes are worth cheering about, seeing such a dramatic transformation can trigger a bittersweet feeling.

Nostalgia is sweet because it momentarily allows us to relive good times, but it’s also bitter because we realize those times will never return. Many early psychological theorists considered nostalgia a bad thing, but modern research shows nostalgic reminiscence can strengthen our sense of personal continuity and remind us we have a store of powerful memories that are deeply intertwined with our identity.

With a respectful nod to campus improvements, let us reflect on a time before Stewart Stadium, when the area it occupies was nothing more than a rugged stretch of undeveloped land in the foothills overlooking Ogden City with the Great Salt Lake shimmering in the distance.

Growing Pains

At the end of World War II, Weber struggled to contain its burgeoning student population at a constrictive downtown Ogden campus. With their minds set on expansion, administrators looked to the hills ... literally. On July 19, 1947, a deed transferring 175 acres of J.M. Mills’ property located east of Harrison Boulevard, between 37th and 40th Street, was made out to Weber College. To fill a gap between the boulevard and Mills’ land boundaries, Weber purchased additional property from Merlin Edvalson later that fall.

A building committee chaired by Wallace D. “Wally” Baddley, superintendent of buildings and grounds, met to discuss building priorities. President H. Aldous Dixon lobbied for an administration building, a heating plant, 80,000-square-feet of classroom space, a library and a stadium. (Prior to having its own stadium, the Wildcat football squad played at Lorin Farr Park, Ogden Stadium and Affleck Park.) As the funding picture became clearer, Dixon had to choose between a library and a stadium, and he chose the latter.

In December 1948, architects Lawrence Olpin, Fred L. Markham and Arthur Grix formalized plans for the upper campus with construction commencing in the fall of 1949.

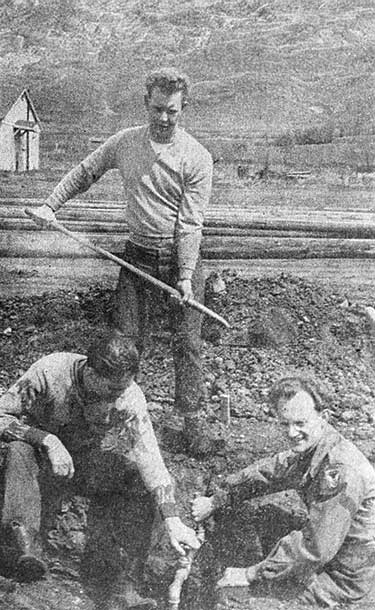

In contrast to today’s building sites, where boundaries are cordoned off and visitors are off limits, student labor was heavily recruited.

Forging the Future

A bold headline in the Jan. 13, 1950, edition of the Signpost student newspaper declared, “STUDENTS! NEW CAMPUS NOW ‘IN YOUR HANDS.’” The issue featured a story about how advanced diesel students used college equipment to contour the shape of the stadium, which saved the school nearly $10,000. The article encouraged more students to get involved.

“There are many things which YOU can do … There are forms to be made and cement to be poured, as well as landscaping to be done,” the newspaper stated.

“There are many things which YOU can do … There are forms to be made and cement to be poured, as well as landscaping to be done,” the newspaper stated.

In the newspaper’s May 5 edition, a large photo of students installing a sprinkling and drainage system demonstrated how Wildcats were “willing to work for what they want.”

During the 1950–51 academic year, Weber students contributed more than 1,000 hours of labor toward stadium and upper campus construction.

Shifting Gears

On Aug. 8, 1953, H. Aldous Dixon left his Weber College presidency to accept a new role as president of Utah State Agricultural College in Logan. Ogden residents had come to rely on Dixon’s strong leadership and support of Weber attaining four-year status. But less than a month later, another strong administrator assumed the mantle of leadership and would remain at Weber’s helm for 19 years, the longest term of any Weber College president.

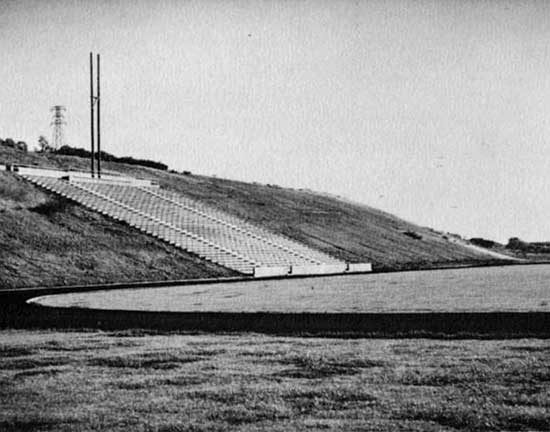

William P. Miller’s first official presidential act was to preside over the dedication of the school’s new football stadium on Sept. 18, 1953. The four upper-campus classroom buildings were not dedicated until the following year on Oct. 27. He and Student Body President John M. Elzey cut a purple and white streamer attached to a wire stretched between goal posts. Former President Dixon offered a dedicatory prayer after which coach Milt Mecham’s Wildcats played San Diego Junior College in a hard-fought contest in their 1953 season opener. An estimated 2,300 fans turned out to watch, with the Signpost boasting in its Oct. 13 issue, “The stadium is one of the best of its kind in the country, with turf to equal that of Rose Bowl specifications and lighting identical to Yankee Stadium in New York.”

In the stadium’s early years, football games had minimal seating; only about 3,700 seats were available on the hillside east of the field. Permanent bleachers were added later, with west stands and a new press box built in 1966.

The following year, a little known slice of school history played a pivotal role in the growth and transformation of not just the stadium, but the entire university.

In January 1967, the college hired alum and advertising agency executive Dean W. Hurst to serve as the school’s first full-time director of the alumni association. He was also charged with leading Weber’s newly authorized development office. The first philanthropic gift Hurst received for the school was a $1,700 grant from the Elveretta Littlefield Wattis Foundation.

“One of the first things I wanted to do was to have some means of attracting possible donors to the school; a place where we could entertain legislators, community leaders, prospective donors and others who might have an interest in the school,” Hurst said.

He noticed the old press box on the east side of the stadium and assumed it was no longer in use. He pitched an idea to transform the space into a VIP box and received a green light from President Miller and Business Vice President James R. Foulger.

He noticed the old press box on the east side of the stadium and assumed it was no longer in use. He pitched an idea to transform the space into a VIP box and received a green light from President Miller and Business Vice President James R. Foulger.

However, Hurst recalls when he went to the building and grounds office and asked superintendent Baddley for a key, Baddley stated, “Dean, you can’t have it! That’s where I store my fertilizer!” Stunned, Hurst replied, “Well, Wally, if I find a different place for the fertilizer, would you consider giving me the key?” Baddley stood his ground with a resounding “No.”

With development officers being tenacious by nature, Hurst didn’t give up. He found a place to store the fertilizer on the south end of the west bleachers and returned to the superintendent’s office with the good news. Baddley still refused to budge. It was only after Hurst appealed to Dean of Faculty Robert A. Clarke that the standoff concluded with the key in Hurst’s hand.

From Storage Shack to President’s Box

Hurst immediately arranged for the college building and grounds crew to paint the interior of the box white. The eastern walls were adorned with photos of NFL football stars, like the Cleveland Browns’ Jim Brown. Then, Hurst and an assistant built a riser for a second row of chairs facing the large plate glass window and installed self-adhesive carpet.

He reached out to Ogden Standard-Examiner owner A.L. “Abe” Glasmann, whose family also owned the defunct Paramount Theatre, which had been called the Alhambra when it opened on Kiesel Avenue in 1915. Glasmann donated 24 theatre chairs, and a college upholstery class reupholstered the chairs in purple fabric. “In all, there was room for 24 guests, a table for snacks and a coat rack,” Hurst said.

Near the entryway, Hurst hung a small donor plaque memorializing Elveretta Littlefield Wattis as the fledgling development fund’s first “official” donor.

Nowadays, with the stadium awash with donor placards denoting key structures and spaces — everything from the Barbara and Rory Youngberg Football Center to Sark’s Boys Gateway to the Larry & Annette Marquardt-Kimball Plaza — it’s hard to imagine a donor sign on campus being a novelty.

“More than anything else, the plaque was just something to recognize donors and let them know how much we appreciate them,” Hurst said. “Before that, there had been very little done at Weber to recognize individuals who had made charitable gifts to the school.”

Hurst’s small, but sincere, investment in donor stewardship reaped dividends. Among the first guests invited inside the newly christened President’s Box was educator and business developer Layton P. Ott, who later donated substantial shares of stock to purchase equipment for the school’s planetarium.

Also on hand for the debut of the President’s Box were avid football fans Donnell and Elizabeth Stewart, who became major contributors to Weber. In fact, on June 11, 1997, Wildcat Stadium was renamed Elizabeth Dee Shaw Stewart Stadium. The fertilizer-storage shack turned President’s Box on the east side of the stadium remained in use throughout the presidencies of William Miller, Joseph Bishop, Rodney Brady, Stephen Nadauld and Paul Thompson, until a 38,000-square-foot Sky Suites & Press Box complex opened on the west side in 2001. The complex features 26 suites, including one used by President Brad Mortensen, along with offices, meeting spaces and study areas for athletes.

Shortly before the 2023 football season, 96-year-old Hurst, curious about the east-side renovation, visited the stadium and surveyed the eastern hillside stripped of its metal benches and former VIP box. More so than a nostalgic longing for what once was, Hurst said he felt humbled and grateful for a fulfilling career made successful by the generosity of others.

Shortly before the 2023 football season, 96-year-old Hurst, curious about the east-side renovation, visited the stadium and surveyed the eastern hillside stripped of its metal benches and former VIP box. More so than a nostalgic longing for what once was, Hurst said he felt humbled and grateful for a fulfilling career made successful by the generosity of others.

“While I was instrumental in securing more than $50 million in gifts to Weber by the time I retired,” Hurst reminisced, “it all began with that small $1,700 grant from the Elveretta Littlefield Wattis Foundation.”