I Can't ... Yet.

Can a small difference in the way we encourage children create adults who persevere?

Amy Hendricks | Marketing & Communications

Photos by Joe Salmond

Jonathan Taylor’s junior year at Weber State University was absolutely disastrous — in his opinion, at least.

“I made two whole C’s,” he says, sipping hot coffee in the Social Science building on a windy October Wednesday. He and his classmates chuckle. The six of them — it’s a small psychology practicum — are sitting in a circle in Room 378. They’re friends. You can tell by the good-natured banter. David Stewart, sitting across from Jonathan, jokes, “I would have thought, ‘Great, those are two classes I don’t have to take over.’” And they all laugh again.

But when Jonathan says, “I seriously ended up going to the counselor because of those two C’s,” they nod in understanding. They’ve been studying mindsets, and they know that behavior is typical of someone with a fixed mindset.

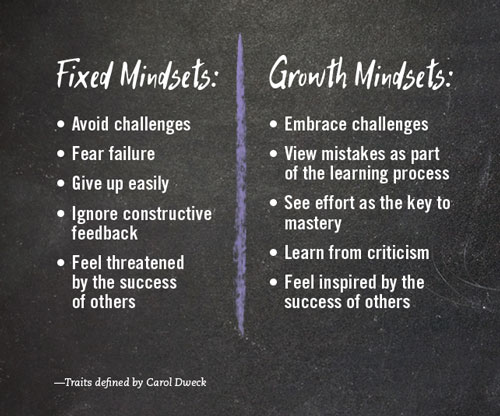

Psychologist Carol Dweck, a Stanford University professor and pioneering researcher in the field of motivation, explains what that is in her book Mindset: The New Psychology of Success: “In a fixed mindset, students believe their basic abilities, their intelligence, their talents, are fixed traits. They have a certain amount and that’s that.”

In other words, they’re born smart or they aren’t. If they aren’t, they believe no amount of hard work or effort will make them smarter. People with fixed mindsets often make remarks like “I’ll never be able to do this” or “I don’t have the genes for this” or worse, “I’m just too dumb. I quit.”

“That type of mindset is damning,” Jonathan says.

Dweck agrees. “Believing that your qualities are carved in stone creates an urgency to prove yourself over and over,” she writes. “Every situation calls for a confirmation of intelligence, personality, or character. Every situation is evaluated: Will I succeed or fail? Will I look smart or dumb? Will I be accepted or rejected? Will I feel like a winner or a loser?”

Fortunately, through the help of a counselor, Jonathan re-evaluated his way of thinking. “I knew I needed to become more open to what I now know to be a growth mindset.”

According to Dweck, people with growth mindsets believe abilities can be developed through dedication and hard work. “Brains and talent are just the starting point,” she writes.

In other words, the more they practice, the more they learn and the smarter they get.

Dweck’s years of research show that students who have growth mindsets exhibit greater motivation in school, earn better grades and score higher on tests.

But how can teachers and parents encourage growth mindsets? Praise effort, not talent, at an early age.

The Power of Yet

Weber State psychology instructors and practicum coordinators Melinda Russell-Stamp and María Parrilla de Kokal call children “active little scientists.”

“If you go with what [developmental psychologist] Jean Piaget thought about cognitive development, kids have this incredible curiosity,” Parrilla de Kokal says. “Biology plays a role, and the environment plays a role, but the fact remains that they’re exploring.”

While people with fixed mindsets believe they are born with a certain level of intelligence, Parrilla de Kokal says she believes environment plays more of a role in how children develop mindset.

“For example, when a child is struggling with math, we as parents say, ‘It’s because you just aren’t a math person, and you get that from me, it’s in your genes,’ we’re telling the child that their intelligence is fixed, that it can’t be grown, that they’ll never be able to do math,” she says.

“What if we instead said, ‘You can’t do that math problem, yet.’ Emphasis on the yet. We’re then telling them that, through hard work and practice, they will be able to do it.”

“Yet” is a word Dweck stresses in her research. In a video lecture hosted by Stanford, she reported on a case study that was performed on 10-year-olds. After being given problems that were too difficult to solve, some reacted positively, others catastrophically, even saying they would go so far as to cheat the next time to make sure they looked smart.

“[For those who reacted negatively], their core intelligence had been tested and devastated. Instead of the power of yet, they were gripped by the tyranny of now,” Dweck says.

During the study, the children’s brains were also monitored. The brains of the children who had more of a growth mindset were “on fire,” Dweck says. “They were processing the error deeply, learning and correcting their errors. The brains of the children with more of a fixed mindset showed no learning. So the questions become, ‘How are we raising our children? Are we raising them for now or yet? Are they focused on the next ‘A’ or are they focused on dreaming big and what they can become?’”

Russell-Stamp, a former school psychologist, heard Dweck present at a conference. “In my previous job, I did a lot of IQ testing. Professor Dweck talked about how, after IQ tests, they’d tell students that their brains could change and grow if they worked hard. I thought that was incredible. She talked about the results and the benefits, and that stuck with me. I think it also stuck because I grew up with a fixed mindset. ‘I can’t’ becomes so ingrained. I thought it would be wonderful to expose children to a growth mindset at a much younger age. Plus, children love to learn about the brain. It’s a big mystery, after all.”

That’s why the Weber State psychology practicum students have been volunteering at local schools and youth organizations — to teach children that intelligence can be developed through hard work, practice and even through mistakes and failures.

In the Classroom

It’s a Monday afternoon in October at Washington Terrace Elementary School. Jonathan and David, along with classmates Etta Chavez and Ashley Allan, file into Tina Allen’s BS ’03 third-grade class, their arms laden with games and activities. “Why do you have a shoe in your pocket?” a boy asks David. “I have too many shoes and not enough feet,” he answers, grinning. “You’ll see in a little while,” he adds.

Russell-Stamp and Parrilla de Kokal are there, too. They remind the children about the worksheet they went over the week before titled “You Can Grow Your Intelligence.”

“Remember last time we talked about the brain and how it can grow if we exercise it, just like a muscle?” Russell-Stamp asks. The kids remember. Allen has reminders all over her classroom — on bulletin boards and posters. “Well, today we’ll show you how.”

Allen splits the class into two groups — one forms a circle with Etta and Ashley, the other with David and Jonathan. Every child is given a notecard with a different question, and they take turns interviewing each other and recording their answers. It goes like this:

What’s your favorite movie? Spiderman.

How many brothers and sisters do you have? Three.

What’s your favorite food? Pizza.

After everyone has had a turn, they mix up the cards and hand them back out. “Now, you ask your question,” Jonathan tells the first student, “and your neighbor will respond with the answer on the back of his card.”

How many brothers and sisters do you have? Spiderman.

What’s your favorite movie? Pizza.

What’s your favorite food? Three.

Hilarity ensues.

“Now, just because we don’t always have the right answers doesn’t mean we’re not smart,” Jonathan says after the children stop giggling. “It’s OK to have a wrong answer sometimes.”

“Can we do that again?” one

student asks.

But the next task waits.

It’s a video clip of the animated movie Big Hero 6, the one where Tadashi, an inventor, is desperately trying to get Baymax, the health-care robot he created, to work. He fails over and over — 84 times, to be exact — before Baymax functions properly.

“What can we learn from Tadashi?” Ashley asks. “That making mistakes is OK. It’s how we learn. And that we should never give up,” she says.

Which finally brings us to the shoe in David’s back pocket. He and Ashley both take turns tying the shoe — Ashley the normal way, David in two swift flicks of his finger. “Are you Houdini?” one student asks, wowed. “No,” David laughs. “Ashley ties shoes one way. I tie shoes another way. One way is a little faster, but neither is wrong. We just tie shoes differently, and that’s OK.”

A Teacher’s Perspective

Allen has been more than happy with the results.

“When one of your students cries because it’s the last day of growth mindset training with Weber State, you know they’ve enjoyed it,”Allen says. It’s now December, and there’s only four days left until the kids go on their holiday break. They should be happy, but one little boy obviously was not.

“The Weber State students generate a lot of excitement for my kids. They’re at that age when they think college kids are just so cool,” Allen says, laughing. “But more importantly, the Weber State students truly do get them excited about working hard.”

Allen has partnered with Weber State for 10+ years on various educational projects. In 2014, however, instructors Parrilla de Kokal and Russell-Stamp shared Dweck’s growth mindset research with her. That’s when they decided to take the partnership in a new direction.

“I knew a little about the mindset theory, just from being in an educational setting, and I’ve been doing some mindset activities in my classroom for many years,” Allen says. “But when we met to discuss it and plan ways to incorporate it into my classroom more, I was really excited because it fits my own beliefs so well. I believe how well you do in class depends on how you feel about yourself, and that can affect your entire life.”

Parrilla de Kokal and Russell-Stamp hope to gather data and analyze how the growth mindset theory has affected Allen’s class. Dweck has seen positive results in schools where growth mindsets are encouraged.

“One teacher took her Harlem kindergarten class, many of whom could not hold a pencil correctly, to the 95th percentile,” Dweck reports. “Another teacher went back to her Native American reservation in the state of Washington and transformed the elementary school in terms of a growth mindset. It had always been at the bottom of the district, at the bottom of the state. Within a year-and-a-half, the kindergarteners and first graders were at the top of the district at reading and reading readiness. That district contained affluent sections of Seattle, so the reservation kids outdid the Microsoft kids.

“They did it because learning a growth mindset transformed the meaning of effort and difficulty. It used to mean they were dumb, now it meant they had a chance to get smarter.”

Allen has seen improvements in her students, too.

“I have one little girl who was going to resource, and she had no idea she could get out of resource until she saw another child do it,” she says. “I told her she could if she worked hard. She put in so much effort after that. She had a goal, and she realized she could do it with effort.”

| A Different Way to Praise | |

|---|---|

| Consistently praising a child’s intelligence — saying “You’re so smart!” for example — can actually make them anxious and ill equipped to handle mistakes, Dweck says. Here are some different ways to praise your child. The dialogue sounds strange, but give it a shot. The key is to be specific. See if it changes your children’s attitude about the challenges they face. | |

| Instead of: | Try this: |

| Good job! | I like the way you kept trying, even when it was hard. |

| You got an A! | All of that practice and extra effort really paid off. |

| You’re so smart! | You’ve worked hard in school. Look where it got you! |

| You’re a great artist. | I like the way you incorporated color and how beautiful your lines are. |

| Math just comes naturally to you. | Now that you’ve worked hard to understand that concept, let’s try something more challenging. |

| You’re a great athlete. | All that extra time practicing free throws really worked, didn’t it? You really helped your team. |

But what about children who aren’t struggling academically?

“We talk a lot about the mindset of children who are behind, but fixed mindsets can happen to children who are already successful in school. They can have an ‘I’m better than everybody’ mentality. That, to me, is just as bad,” Allen says.

“When those children reach a point where they do start to struggle — and we all struggle at some point — it’s devastating for them. My brother was a perfect example. He always did really well in school, and it wasn’t until he got into Calculus 2 in college that he started to struggle. He felt like a failure. He couldn’t bend. That’s why I believe it’s so important to start encouraging growth mindset at an early age.”

Allen believes children need to struggle to be successful.

“They need to be challenged,” she says. “There always needs to be a ‘next thing,’ a next level that’s hard for them. If they are allowed to struggle, they’ll be much more well-rounded adults.”

Team Spirit

An unexpected result has been that Allen’s class is now much more team-oriented.

“It’s more cooperative,” she says. “If someone is struggling, we talk about what we can do to get all of our team to the next level. There’s never just one star.”

Jonathan says that’s something he had hoped to see. “Sometimes kids can say things that are, for the most part, unintentionally cruel. They’ll say things like, ‘That student can’t read’ or ‘He can’t do that.’ We can’t necessarily make kids stop, but we can add the word ‘yet.’ That helps the child they’re talking about, but it makes the child saying it think, too.”

Parrilla de Kokal had an anecdote just for that.

“What came to mind — as pathetic as it is — if you remember Sleeping Beauty, and this is a loose association, just stay with me,” she tells her laughing psychology students. “It’s the scene of baby Aurora’s christening. The evil witch wasn’t invited. Mad, she tells the king that Aurora will one day hit the spindle of a spinning wheel and die. They couldn’t change that she did that, but the good fairies altered her spell. Instead of dying, she would sleep, then Prince Charming would come and rescue her. For our purposes, it’s like that. We’re the good fairies. We can’t undo what is said, but we can change it so it has a positive outcome.”

Parrilla de Kokal says the mindset theory does not diminish the fact that some people have a natural disposition toward something, but even those people have to put in a lot of effort. “I don’t have the pipes Beyoncé does,” she says, smiling. “I will never sing like she does. But I can certainly sing better than I currently do if I wanted to go through the effort of doing that. If I don’t try because I’m afraid I’ll be a loser, I may never know that I actually can sing.

“We want our kids to hope they can do better, to try to do better, to try new things. Beyoncé sure tried. Michael Jordan sure tried. He didn’t even make his high school varsity basketball team on the first try, but his failure motivated him to work harder and get better. Steve Jobs got fired from his own company, only to be rehired later and become incredibly successful. These are great lessons for our children.”