CAUTION: Opioid

Risk of Overdose, Addiction

Amy Renner Hendricks | Marketing & Communications

On Sept. 29, 2007, Weber State University football player Derek Johnson suited up for the fourth game of the year.

It was looking to be a promising season for the 290-pound nose guard, who, in three games, already had 10 unassisted tackles — just one fewer than he had in all of 2006. He took the field in Missoula, Montana, with one goal: Beat The Griz. An illegal chop block by a Montana player early in the game dashed Johnson’s hopes, ruined his knees, ended his season and set into motion a series of events that would almost end his life … multiple times.

Over the course of eight surgeries, Johnson became hooked on prescription opioids, a class of drugs that includes prescription pain relievers such as oxycodone, hydrocodone, codeine and others.

After the prescriptions ran out, he turned to another opioid, an illegal one — heroin.

That’s the nature of the opioid beast.

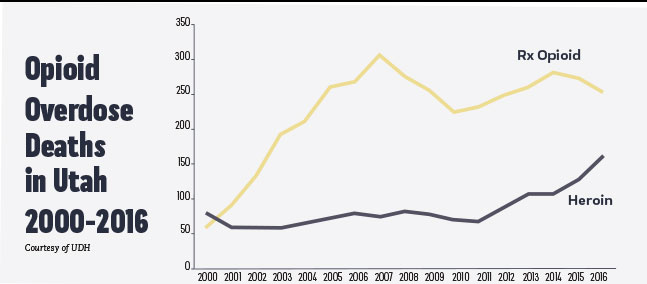

Prescription opioids and heroin are chemically similar. UDH reports that 80 percent of heroin users started with prescription opioids.

Prescription opioids and heroin are chemically similar. UDH reports that 80 percent of heroin users started with prescription opioids.

Johnson’s 11-year struggle with addiction is no secret. In the summer of 2018, he shared his story with local media during the Ron McBride Foundation’s 2018 Love You Man Golf Tournament. “I probably had three or four rock bottoms,” Johnson told local reporters. “Every time you relapse, it gets a little bit worse.”

His mother, Denece, was with him at the event. She tearfully explained that she didn’t know the signs of a heroin problem. “I didn’t know finding a silver spoon that was burnt on the bottom meant something (spoons are often used to ‘cook’ heroin),” Denece said, “or that aluminum foil in his bedroom meant something (foil contains the drug while it is smoked).”

Johnson’s former Weber State football coach, Ron McBride, was there, too. The Ron McBride Foundation has now joined the fight against opioid addiction.

The foundation supports a number of educational-related causes, including rebuilding libraries and reading programs, but opioid education is something “we just kind of fell into,” McBride said. “The more you talk to people in education, to principals, to teachers, to parents, you see this is part of our responsibility.”

How Did the U.S. Get Here?

It’s hard to say exactly. We now know that prescription opioids are highly addictive, but that’s not how pharmaceutical companies originally marketed the drugs. According to the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services website, pharmaceutical companies in the late 1990s “reassured the medical community that patients would not become addicted to prescription opioid pain relievers, and healthcare providers began to prescribe them at greater rates.”

The amount of opioids prescribed in the U.S. peaked in 2010, then decreased each year through 2015, according to the CDC.

However, the amount of opioids prescribed in 2015 was still three times higher than in 1999 — enough for “every American to be medicated around the clock for three weeks.”

While the opioid crisis has been in the making for decades, it wasn’t declared a public health emergency until October 2017. Today, it makes the news on a daily basis. There are billboards about opioids throughout Utah, and just across the street from WSU’s Ogden campus, the McKay-Dee Surgery Center and Orthopedics clinic has big banners in its windows that read, “Opioids: Physical dependency can happen in just seven days.”

However, the amount of opioids prescribed in 2015 was still three times higher than in 1999 — enough for “every American to be medicated around the clock for three weeks.”

Warning signs are everywhere, which leads to the question: Should opioids be prescribed at all for pain?

J.D. Speth BS ’11, a WSU psychology alumnus who earned his Doctor of Pharmacy degree from Pacific University, is a community pharmacist for Intermountain Healthcare. “Yes, opioids have their place,” he said. “If prescribed, monitored and used properly, they are not evil. In fact, they can help many people. However, patients need to be educated about the risks, not just with opiates, but with every medication.You can die from an opiate. You can also die from a bloodthinner.”

In 2016, the CDC released its Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain, which includes the following recommendations for healthcare providers:

- Use opioids only when benefits are likely to outweigh risks;

- Start with the lowest effective dose and prescribe only the number of days that the pain is expected to be severe; and

- Reassess benefits and risks if considering dose increases.

The CDC also recommends that prescribers use state-based prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs) to identify patients at risk of addiction or overdose.

“Every controlled substance that an individual gets from a retail pharmacy is logged,” Speth explained. “If a person comes in with a prescription for a large amount of oxycodone or a very high dose of the drug, I can log on to the database and check his or her prescriptions. I might see that, in addition to oxycodone, this person has gotten Percocet from the dentist and Lortab from a surgeon and morphine from another specialist. I can also see that they’ve gotten some early refills.At that point, I can counsel the patient, or even refuse to fill the prescript

Speth said he has noticed the number of opioid prescriptions going down, at least somewhat. He explained that much of the misuse and abuse, sadly, comes from diversion — when prescription drugs are obtained or used illegally. He cites the statewide Use Only As Directed campaign, which reports that friends and family members supply two-thirds of all the opioids misused and abused by Utahns.

My advice is, when prescribed opioids, only take exactly what you need for pain and then safely dispose of the rest. So many times we think, ‘Oh, I’ll save these for a rainy day.’ Then they become a danger. What if your teenage daughter’s friend comes over and takes them? What if your friend is in pain and you offer them some of your pills? At that point, you’re not using the drugs for what they’re prescribed for. The safest thing to do is just get rid of them.”

Find out how to safely dispose of your unused or expired prescription opioids at useonlyasdirected.org.

Alternatives to Opioids

Courtesy of UDH

Acetaminophen (Tylenol)

Ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin)

Physical Therapy

Exercise

Massage Therapy

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

Medication for Depression or Seizures

Interventional Therapies (Injections)

Don’t Become a Statistic

The CDC suggests there are safer approaches to prescription opioids that may be as or more effective in relieving pain — a subject that interested Ethan Erickson BS ’17. As an undergraduate majoring in athletic therapy, Erickson conducted research alongside Layton oral surgeon Todd Liston BA ’86 that tested the ability of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) to decrease patients’ pain following wisdom tooth extractions.

The results showed that PRP injections into the extraction site did not reduce the perception of pain. During the study, Liston and his partners prescribed the opioid Tramadol. Interestingly, patients only took three to four pills total and managed the rest of their pain with over-the-counter medications like acetaminophen or ibuprofen.

“This led to leftovers of the Tramadol, which can create potential for abuse,” said Erickson, who is currently in his first year of medical school at the University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio. “The surgeons are now much more mindful of the amount of opioids they prescribe.”

While it may be difficult to reject opioids after major surgeries, be sure to talk to your doctor about the risks and don’t be afraid to ask about alternatives.

The Need for Needle Exchanges

A spike in heroin use, which some believe is directly connected to the opioid crisis, has intensified the need for needle exchange programs — community-based programs that provide access to sterile needles free of cost. The first needle exchange effort in Ogden was held in September 2017. Mindy Vincent organized the program. Vincent, coincidentally, was a guest lecturer for a WSU Health Administrative Services class earlier that year. She is not one to mince words.

Per the Center on Addiction:

An opiate is a drug naturally derived from the flowering opium poppy plant.

Opioid is a broader term that includes opiates and refers to any substance — natural or synthetic — that binds to the brain’s opioid receptors, which control pain, reward and addictive behaviors.

All opiates are opioids; not all opioids are opiates. And, just because opiates are natural does not mean they are less harmful.

Common Opioids

(Semi-synthetic drugs with opium or morphine-like pharmacalogical action)

Oxycodone (e.g., Oxycontin, Roxicondone)

Oxycodone/Acetaminophen (e.g., Percocet, Roxicet)

Hydrocodone/Acetaminophen (e.g., Lortab, Vicodin, Norco)

Tramadol Fentanyl Hydromorphone (e.g., Dilaudid, Exalgo)

Meperidine (e.g., Demerol)

Methadone

COMMON OPIATES

(Refers to the alkaloids only found naturally in opium)

Heroin

Opium

Codeine

Morphine

“By the second use, a needle looks like barbed wire. By the sixth, it looks like a shark’s mouth,” Vincent said during the lecture, coaxing the class to “Google it.” Curiosity got the better of some students, so they pulled out their phones to find, to their horror, that she was right.

It’s shocking to most, but not to Vincent, a licensed clinical social worker and the executive director of the Utah Harm Reduction Coalition. A nonprofit, community-based organization, the coalition provides “evidence-based interventions to help people reduce health and social harms associated with substance use.”

Vincent can tell you a lot about needles and addicts. For example, most addicts don’t care how many times a needle has been used. They don’t even care if they use tourniquets (a long strip of plastic tied around the arm to raise the vein). “And when they don’t use tourniquets, they fish to find the vein,” she said. “That can cause infections, abscesses, endocarditis (an infection of the heart valves or inner lining).”

Vincent knows these things from her job, of course, but also because she was addicted to intravenous (IV) drugs for 17 years, and because her brother was addicted to heroin, and because her sister died from an opioid overdose. She worked with local law enforcement agencies to develop the needle exchange program in Ogden (downtown Ogden alone had the highest per-capita rate of opioid deaths in Utah in 2014 and 2015, according to the state).

The program, which is also present in Salt Lake and Tooele counties, helps remove contaminated syringes from circulation, but it also introduces users to people like Vincent, who can educate them on overdose prevention, refer them to medical, mental health and social services, and offer them information on substance use disorder treatment.

Danielle Croyle BS ’86, a former Ogden City Police captain, is a proponent of community-based programs like needle exchanges. “We, as law enforcers, are compassionate, empathetic. The opioid crisis is complex, and, as with any social issue, multifaceted. I believe community-based programs are beneficial and should be there to help those who need help. Addiction is a disease. Unfortunately, at times, it is a disease that comes with a criminal element. The role of police in the opioid crisis is to ensure laws are adhered to, for the safety of all the people in our community.

“Police work to prevent opioids from being distributed illegally, to make sure distributors are not able to set up shop in Ogden. At the same time, they also respond to many calls about drug overdoses and, sadly, unattended deaths (when people die alone and are discovered later). As first-responders, we carry naloxone (a drug to reverse overdoses), and police officers are trained in how to administer it.”

On the ground level, Croyle has seen the number of opioid offenses increase in recent years. “There are entire task forces to investigate drug abuses,” she said. “Again, police officers, have to enforce the laws on the books. The legislative branch creates those laws. The judicial branch applies the laws. The community-based programs create initiatives to help those who need help. The opioid crisis involves everyone.”

Most recently, the media has focused on states, cities and counties that are suing prescription opioid manufacturers for aggressively marketing the drugs and downplaying the possibility of addiction. The state of Utah has joined the fight, as has several of its counties, Weber and Davis counties included. Basically, litigants want Big Pharma to reimburse communities for the high costs associated with fighting the crisis.

Reaching Out

Justine Murray BS ’15 is the program manager for another community-based program that is on the frontlines of the opioid fight. Youth Futures Ogden is a shelter for vulnerable and homeless youth, but the organization also offers street outreach to both youths and adults. Murray and her team go two times a week to strategic locations in search of youths in need. It’sthere where Murray and her team most often encounter people — mostly adults — with addictions. Even though most are over 18, Youth Futures helps them by giving them naloxone kits.

“We give them the tools to save their own lives or someone else’s,” Murray said. “The next week, we follow up with them if we can. These people are struggling, and they know they’re struggling. We simply ask them, ‘What can we do to help you today?’ Sometimes, they just need a friendly conversation, but oftentimes those little steps, that building of a rapport, is just what they need to eventually get the help they need in their fight against addiction.”

Murray has a unique perspective. A double major in criminal justice and social work, she focuses on rehabilitation, not punitive measures. “The punitive side of criminal justice is valid and needed. If you break a law, there absolutely has to be a consequence,” she said. “However, I feel like we need to do better on the rehabilitative side.”

She believes Utah is making strides. She cited Utah House Bill 119 as an example. Passed in 2014, the bill, known as a Good Samaritan law, establishes immunity for the good faith administration of naloxone. Basically, if you administer naloxone to someone in an effort to save his or her life, and call 911, you cannot get in trouble, even if you have legal problems. The police will address the person who overdosed, not the person who administered the naloxone.

While Murray hasn’t seen many youths addicted to opioids, she has seen families torn apart by drugs. “Most often, the kids who come to our shelter are phenomenal kids,” she said. “They’re great kids who have lost their support systems. Many times they’ve lost their support systems to drugs, and that’s a whole different trauma.”

Murray sees things every day that break her heart, but she loves her clients. She says the best thing we can do in this crisis is stay openminded.

“This is happening everywhere. This isn’t just a Downtown Ogden or Downtown Salt Lake problem. Everyone is being impacted. Don’t be closed off to people who are struggling with addiction. Be a listening ear. Hear people’s stories and struggles. Without support, people with addictions have no chance. None.”

Editor’s Note: This story barely touches the multifaceted opioid crisis in the U.S. There are still the stories of the underground networks of drug dealers, the significant and dangerous drug busts, the demographics involved in the crisis, the controversial solutions (medical marijuana, for example). It’s far too complicated to include in one article, in one magazine even; however, Weber State University has trained/is training an army of people — from social workers, to pharmacists, to doctors, to nurses, to law enforcement officers, to judges, to lawmakers — who will contribute their expertise to battle this crisis.