The Curious Case of the Anonymous Windfall

Karin Hurst, Jaime Winston and Amy Renner Hendricks | Marketing & Communications

Intro

The story of Weber State University’s 125th anniversary campaign begins like a mystery novel (minus the demise of a wealthy recluse or the discovery of a secret staircase or the sudden onset of a violent rainstorm). But there was a cryptic message … and a cliffhanger: Who sent University Advancement Vice President Brad Mortensen a letter promising $3 million on the condition that no one attempts to identify the anonymous benefactor?

It would have been a tantalizing whodunit for literary sleuths like Nancy Drew, Hercule Poirot and Sherlock Holmes, but Mortensen, being a shrewd, levelheaded, you-can’t-pull-the-wool-over-my-eyes kind of guy, suspected a hoax. As did then-President Ann Millner. As did legal counsel Rich Hill, who, nevertheless, told Mortensen that he didn’t see any harm in following through.

So, Mortensen signed the agreement, FedExed it back to a bank in Denver and waited, albeit skeptically, for something to happen. Several days later, on a misty March morning, two honest-to-goodness checks arrived, each payable to WSU and totaling $3 million.

And that’s pretty much how Dream 125: The Campaign for Weber State was born. More serendipity than strategy. It was 2009 — seven years since the school’s Changing Minds Together campaign had reeled in an unprecedented $96 million. A burgeoning surplus of students was now stretching the limits of university resources; leading educational trends were demanding more undergraduate research opportunities, study abroad programs and service-learning internships; and nearly everyone on campus was yearning for a brand spanking new, world-class facility to replace the dilapidated, seismically vulnerable, architectural fossil that served as a science lab.

School administrators held preliminary conversations about ramping up for another big fundraiser. They even a hired a professional consultant and assembled a zealous campaign advisory council comprised of campus and community leaders who, despite America being in the throes of its worst financial crisis since the Great Depression of 1929, lobbied for an unfathomable $150 million campaign goal. But no final decisions were made until that fortuitous, multimillion-dollar gift materialized, and Mortensen and his team concluded that when $3 million falls from the sky, it’s time to make a move!

It was hastily determined that the public phase of the campaign would coincide with the 125th anniversary of the university’s founding on Jan. 7, 1889. The fundraising goal would be $125 million, one million for each year of Weber’s existence.

The ensuing hullabaloo sent development officers scrambling to match university needs with donor interests, while campaign planners racked their brains for a suitable name. SOAR? (Naw. Folks over at the Dumke College of Health Professions said SOAR made them think of SORE.) CATALYST? (Nope. Chemistry faculty argued that a catalyst is something that speeds up a chemical reaction, but remains unchanged. Since the goal of any fundraising campaign is change, why would we choose such a counterintuitive name?) DREAM? (Hmmmmm…let’s think about that one. Dreams are powerful, inspiring, motivating. They help us achieve remarkable things. Whether a scrappy kid from Oakland, California, wants to become an NBA All-Star, or a junior college dropout wants a second chance and an opportunity to help a war-torn African nation heal, or a young woman wants to pursue the dental hygienist career her cancer-stricken older sister could never have, the first step is to dream.) Yes, DREAM sounded like a great fit. (And besides, our new president, Chuck Wight, really, really liked it.) And so, it began.

Pulling off the most ambitious fundraiser in school history required planning, persistence and pie charts, strategy and happenstance, trust and heart. A total of 16,640 humanitarians opened their hearts and their wallets to make possible $164,392,217 worth of campus miracles like: the Dream Weber program, which, last year alone, empowered 2,476 low-income students to attend WSU; the colossal, 184,564-square-foot Tracy Hall Science Center, which lends a breathtaking backdrop to a stellar science and math education; the cutting-edge technology that frees hundreds of hearing-impaired patrons from having to wear bulky, conspicuous hearing-assistive devices at Browning Center performances; and the record-setting pledge that nudges the outdated Social Science building one step closer to a 21st century facelift.

It is a bogus assumption that all Dream 125 supporters were millionaires. They weren’t. In fact, an eleventh-hour push for student donations laid a solid foundation for future student-fundraising efforts. The notion of student philanthropy is a tough nut to crack. Most students feel they’ve already done their part by paying tuition. So, during Dream 125, when 2,302 students bled a little “green” (donating more than $131,000) to prove they bleed purple — that meant a lot. Because the truth is, whether you have an anonymous donor who gives you $3 million or a history student who gives you $10, every gift to Weber State University is personal and important. Every gift comes from the heart and speaks volumes about how treasured this institution is.

From its mysterious start to its triumphant conclusion, Dream 125 was a campaign of love, sacrifice, vision, respect, loyalty and a university’s indefatigable determination to be prepared to fulfill dreams for future generations …

Chapter 1

Chapter 1

Two Dreams Fulfilled

Stephanie Carranza BS ’15 couldn’t complain while earning her bachelor’s degree, despite the numerous classes, clinical hours and exams. Not with the memory of her sister, Pamela Carranza AS ’09, BS ’11, to inspire her.

“She was able to pass all of her classes, pass all of her exams and take her boards, while on chemotherapy,” Stephanie said. “That’s hard for students to do when they’re 100 percent complete.”

Pamela fell ill in the summer of 2009, before her senior year in WSU’s dental hygiene program. First, she was diagnosed with acid reflux, and, after collapsing at a movie theater, a blood clot.

Then the Carranza family discovered it was something else.

Then the Carranza family discovered it was something else.

At Huntsman Cancer Institute, Pamela learned she had angiosarcoma, a cancer of the blood vessels, in her heart and metastasis to the lungs. “They put her on extremely aggressive chemo,” Stephanie said. Pamela also received oxygen treatment, surgeries and experimental treatments. She returned to WSU in the fall of 2010. Her cancer cleared up, then returned a month later. Pamela died in the spring of 2011 at age 23.

“She was one of the hardest-working people you could ever meet,” said Stephanie, who accompanied Pamela to class to take notes, carry books and push her wheelchair.

She also took over Pamela’s duties as a dental hygiene assistant at a Brigham City clinic, where she learned she loved the subject. “I said, ‘This is definitely what I want to do,’” Stephanie recalled.

Inspired by her sister’s courage, Stephanie joined WSU’s program in 2014.

“Both sisters really embraced the idea of being a university student and being involved as much as they possibly could,” said Stephanie Bossenberger AS ’78, BS ’81, dental hygiene department chair.

When Bossenberger heard Pamela (who had earned enough credits to receive her bachelor’s degree) would pass away prior to graduation, she arranged an impromptu ceremony in her hospital room with cords, a dental program pin and diploma. Pamela died two days later.

During the Dream 125 campaign, an anonymous donor created the Pamela M. Carranza Memorial Scholarship to support students in the Dr. Ezekiel R. Dumke College of Health Professions who are earning bachelor’s degrees in dental hygiene. To date, three deserving students have received the scholarship.

During the Dream 125 campaign, an anonymous donor created the Pamela M. Carranza Memorial Scholarship to support students in the Dr. Ezekiel R. Dumke College of Health Professions who are earning bachelor’s degrees in dental hygiene. To date, three deserving students have received the scholarship.

And that brings a smile to Stephanie’s face. She’s proud that her sister’s memory is being honored. A scholarship recipient herself — Stephanie received both the Stephanie Bossenberger Dental Hygiene Scholarship and a scholarship from the Department of Dental Hygiene — she knows how helpful financial assistance can be for students trying to achieve their dreams.

Chapter 2

Chapter 2

Unwavering

For 79* straight months, Chantel Smith BA ’06 has sent small gifts to her alma mater. Her donations go to the University Excellence Fund, where they help meet Weber State’s greatest needs, and to the history fund in the College of Social & Behavioral Sciences, where Smith spent four years earning her history degree.

Smith gives through automatic monthly withdrawals.

Smith gives through automatic monthly withdrawals.

“If there are going to be things that I forget, or things that fall off my plate because I’m simply too busy, one of those things will never be my support,” she said. “It also allows me to stay personally invested in the university when I’m too far away to be there in person.”

Another thing Smith, who was a first-generation student, will never forget is the C+ she received in associate professor Stephen Francis’ BA ’91 German history class. “I had never received a C in my life,” she said. Looking back, she realizes that C was actually good for her. “It set the tone. I knew I couldn’t just get by; rather I had to really work on my research. That was really impactful to me.”

She also remembers associate history professor LaRae Larkin, who pushed her to achieve, and history professor Kathryn L. MacKay, who led Smith’s class in crafting a teepee out of actual buffalo hide.

Today, Smith works at the College of William & Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia. She is the director of development for the finance/marketing programs in the Raymond A. Mason School of Business.

Smith’s gifts open doors for students to learn valuable lessons like she did.

“In many large institutions, you don’t get that one-on-one time with faculty members,” Smith said. “My time at Weber State was an incredible experience. I want others to have that opportunity, too.”

*At time of posting

Chapter 3

Chapter 3

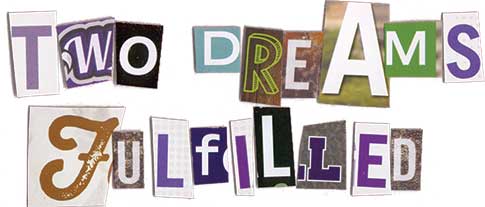

The Man Behind the Record-Setting Gift

One of the most important things to know about alumnus John E. Lindquist is that the E is not optional. “That is absolutely correct,” said Lindquist. “If you call me John, I’ll punch you,” he chided with a playful grin that belied the flint in his voice. “It started when I was a little boy using the name Johnny,” Lindquist recalled. “One day my dad said, ‘You know, Johnny’s not your name.’” The elder Lindquist (also named John) explained that with his son’s middle initial being E for Ellis, John E. and Johnny sounded alike.

One of the most important things to know about alumnus John E. Lindquist is that the E is not optional. “That is absolutely correct,” said Lindquist. “If you call me John, I’ll punch you,” he chided with a playful grin that belied the flint in his voice. “It started when I was a little boy using the name Johnny,” Lindquist recalled. “One day my dad said, ‘You know, Johnny’s not your name.’” The elder Lindquist (also named John) explained that with his son’s middle initial being E for Ellis, John E. and Johnny sounded alike.

Names from the Lindquist family tree can get awfully confusing. There’s John E.’s son, John Aaron, who’s named after his grandfather, John Aaron. “And his son has my father’s father’s name, which is Charles John Aaron Lindquist,” said John E., whose second grandson was named John. The Lindquist women are nearly as guilty. John E.’s mother, sister and niece were all named Telitha after his maternal grandmother, Telitha Browning.

While the spelling of John E.’s name may have caused moments of childhood confusion, he never second-guessed what he’d be when he grew up. “I always, always wanted to be a mortician,” he insisted. (Not a doctor. Not a firefighter. A mortician.) Given that three generations of Lindquists before him had been in the funeral business, you’d think it would have been a goal easily achieved. It wasn’t.

“My father used to say, ‘I’m not going to create a job for you,’” Lindquist recalled. “He wanted us to have our own lives.” As a kid, John E. did yardwork near the cemetery offices, but was rarely allowed to enter the buildings. Year after year, Lindquist’s father refused to hire him.

At 18, while awaiting active duty in the U.S. Army, John E. was finally invited to join the family business. “The main reason was that they were doing a bunch of remodeling, and they needed a cleanup guy,” he insisted. “I did everything no one else would do and never complained, but when I came back from active duty, my father wouldn’t have me back.”

It wasn’t until 1971, after John E. had graduated from the California College of Mortuary Science, that John A. finally relented and brought his son on full time. (That’s when those middle initials really came in handy. It was the only way coworkers could distinguish which of the two John Lindquists they were referring to.)

John E. and John A., who passed away in 2013, may not have always agreed on career paths, but they certainly shared a legendary passion for Ogden and Weber State University. “Dad used to say that people have an obligation to give back to where they got their start, and I really believe that,” said Lindquist, who is especially proud of his Ogden heritage. “Years ago, I made an absolute, conscious decision to never not live in Ogden,” he stated. “I lived other places briefly, but my residence was always Ogden.”

And because Weber State University is located in the city he loves, Lindquist worked several years to finagle a record-setting gift to help remodel the Social Science building, a project that, in all honesty, he has no deep, personal interest in. (Which makes his gift all the more impressive.) “Brad Mortensen (WSU’s vice president of University Advancement) and President Chuck said that was the building that needed to be fixed,” he stated matter-of-factly. “So I said, ‘Fine.’” Simple as that. His local university had a need, so John E. stepped up to the plate.

Throughout the upcoming renovation, there is one thing that Lindquist will insist upon. He is adamant that the finished building be christened Lindquist Hall, not John E. Lindquist Hall. He prefers a name that represents all Lindquists — regardless of middle initials.

Chapter 4

Chapter 4

Building for the Future

For this story, we’re going to have to ask that you use your imaginations. During the Dream 125 campaign, Weber State’s College of Engineering, Applied Science & Technology (EAST) was given a significant gift, one that set the brilliant minds within the college swirling with excitement for it provides the seed money for a new, spacious, high-tech, sustainable building.

“Thanks to this wonderful donation from the Ray and Tye Noorda Foundation, we know that a state-of-the-art facility is in our not-too-distant future,” said David Ferro, dean of EAST. “We don’t know exactly what it will look like, but we know it will be constructed with sustainability in mind. It will provide a much-needed home for our students, faculty and staff to pursue projects in areas like renewable energy. It will also give us opportunities to sponsor even more outreach activities to encourage young people into engineering.”

In recent years, EAST professors have been exploring solar projects with their students and adding renewable energy classes to their curriculum.

For example, since 2011, students in associate electronics engineering professor Julie McCulley’s BS ’89, BS ’05 courses have designed and developed Mobile Elemental Power Plants (MEPPs) — mobile generators that run on alternative energy. The mini-power station fits on a 10-foot trailer and replaces traditional generators used for camping or as back-up power sources. MEPPs could even be used in disaster relief efforts.

Another project, led by Fred Chiou, associate electronics engineering professor, and his team of students, also harnessed the power of the sun. The group designed and built a solar charging station on campus to power electric bicycles and motorcycles. Chiou hopes the project will encourage students to use more sustainable methods of transportation, thus eliminating some of the emissions from gasoline-powered cars.

The college’s dedication to sustainability appealed to members of the Ray and Tye Noorda Foundation, which generously donated the money that will help make EAST’s building become a reality. One of the missions of the foundation is to “leave the world better than we found it, or at least no worse.”

“The plans for the new building, and the many projects and courses that students and faculty are involved in, show that the college truly takes to heart the responsibility of being a school that benefits its students and both the local and broad (worldwide) community,” said board member Kathy Noorda, daughter of the late John Noorda, who was the son of the late Ray and Tye Noorda.

“The plans for the new building, and the many projects and courses that students and faculty are involved in, show that the college truly takes to heart the responsibility of being a school that benefits its students and both the local and broad (worldwide) community,” said board member Kathy Noorda, daughter of the late John Noorda, who was the son of the late Ray and Tye Noorda.

Kathy said her father, who enjoyed being in nature and didn’t want that experience to be nonexistent for future generations, often talked about how the developed world was using fossil fuels at a deathly rate. “He said, more than once, ‘Our grandchildren are going to curse us in our graves for having burned it all up.’ He worried about how burning it would impact the environment. He also believed that fossil fuels were incredibly versatile and their uses in the future (beyond just plastic bags) were yet to come, but those developing technologies would never happen if the fuels were gone.”

Kathy said that passion for sustainability is directly in line with philanthropy. “Love of humans, the original meaning of the word philanthropy, must include the self-preservation of all people. Since we exist today and thrive because of our environment, it just makes sense that philanthropy includes concern of the planet and its non-human inhabitants that make the balance of our existence possible.”

Chapter 5

Chapter 5

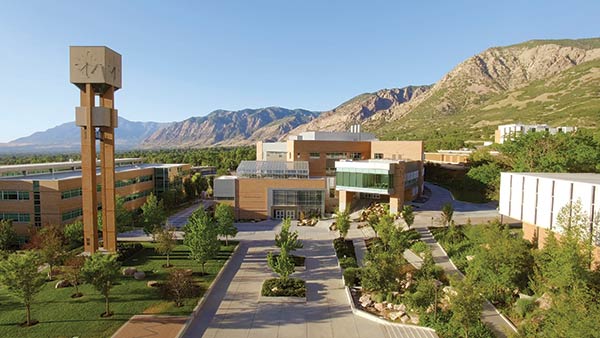

A Jewel at the Heart of Campus

It’s massive. It’s modern. It’s a dream come true for Weber State University.

After a VIP-studded ribbon-cutting ceremony on August 24, the $77 million-dollar Tracy Hall Science Center is officially open. And what a gem it is! A dazzling, 21st century backdrop for a stellar science and mathematics education.

Named in honor of H. Tracy Hall ’39, alumnus, scientist and inventor of the laboratory process for making synthetic diamonds, the 189,544-square-foot science center merges the wonders of science with the beauty of nature. Painstaking design details include exterior bricks that mimic DNA sequencing; cast slabs of abstract patterns associated with each of the seven academic departments within the College of Science; and a 40-foot sculpted wall of running water inspired by a Weber Canyon geological formation known as the Devil’s Slide. A labyrinth of interior and exterior plate-glass windows allows passersby to see science in action.

Dominating the first-floor lobby, near the southwest entrance, is an imposing metal cube sure to capture the attention of every first-time visitor. What looks like the provocative artwork of Pablo Picasso is actually the 8-ton, solid stainless steel core of a working diamond press designed by H. Tracy Hall, and donated by his son, David.

David Hall envisions the new building as a popular place for students to gather, communicate, debate and learn. “My hope is that students will often say, ‘Let’s go meet at Tracy Hall,’” he said. Hall also encourages hands-on exploration of the enormous cube. “I’ve put this great big press there hoping people will climb all over it and take pictures. The neat thing about a great big chunk of steel is you’re not going to be able to wear it away too much; you’re not going to get rid of it.”

Not quite so noticeable, but equally significant, is an oak plaque near the entrance of a first-floor student lounge. It lists 99 names of groups or individuals — most of them science and math students — who each contributed $50 toward the completion of Tracy Hall during the final months of the Dream 125 campaign. To Brad Mortensen, vice president of University Advancement, each name represents a breakthrough in creating a culture of student philanthropy on campus. “We’re very sensitive to the price students pay for tuition,” Mortensen said. “But, throughout the campaign, we also tried to plant in their minds the notion that if a lot of them gave just a little, they could make a university education possible for someone who is financially worse off than they are. And that idea really resonated with our students.”

The Tracy Hall Science Center is the largest building on campus and strategically located. “We situated this open, inviting building purposely, so that students will walk through it from parking lots to the center of campus,” said Mark Halverson BS ’06, MBA ’10, associate vice president for facilities and campus planning. “Tracy Hall Science Center is a jewel at the heart of campus. It gets everyone excited about science and math.”

Tracy Hall Science Center by the Numbers

- 2 research towers

- 4 floors

- 14 classrooms

- 20 research laboratories

- 25 teaching laboratories

- 88 full-time faculty & staff

- 294 rooms

- 600 tons of structural steel

- 11,554 yards of concrete

- 258,752 bricks

Chapter 6

Chapter 6

The Theater, the Theater

Cassie Burton, a local elementary school theater teacher, arrived at Weber State’s Val A. Browning Center for the Performing Arts carrying an enormous box of costumes. “I made most of these,” Cassie said waving away a rebellious octopus arm, “with a lot of help from my students’ moms — and even my mom.”

The costumes had been used in the March 2016 Twisted Fairy Tale Festival at Ogden High School. The festival featured hundreds of children from four elementary schools in the Ogden School District, including Wasatch, Polk, Shadow Valley and Taylor Canyon. Burton, who works with Wasatch and Polk, wrote and directed a number of the acts, including a tangled up version of The Little Mermaid.

The costumes had been used in the March 2016 Twisted Fairy Tale Festival at Ogden High School. The festival featured hundreds of children from four elementary schools in the Ogden School District, including Wasatch, Polk, Shadow Valley and Taylor Canyon. Burton, who works with Wasatch and Polk, wrote and directed a number of the acts, including a tangled up version of The Little Mermaid.

Burton was at the Browning Center to reunite with one of her actresses, Megan Aardema from Wasatch, and to meet other children from Shadow Valley. Despite the many months that had passed since the festival, Megan, who played a mermaid but was enjoying trying on the octopus costume, still remembered her lines …

“Oh my gosh! I am SO frightened. The sea witch is loose in the kingdom!’”

And …

“Can you imagine walking on those two wobbly things?!” (Talking about human legs, of course).

As Megan delivered her lines, she became a different child. Having been quiet earlier that morning, suddenly her voice projected. “My lines were supposed to be sassy,” she said, smiling. “I added even more sass to them.”

Burton, who is a Beverley Taylor Sorenson Arts Learning Program arts specialist, was proud. “I tell my kids they can be anyone they want to be on that stage,” she said. “I was shy in elementary school. I lucked into a theater program where I had a teacher who said, ‘You CAN do this.’ I want to be that teacher for someone.”

The Beverley Taylor Sorenson Arts Learning Program, named for a beloved Utah philanthropist who passed away in 2013, helps fund the salaries of arts specialists, like Burton, in elementary schools across Utah. In 2013, the Sorenson Legacy Foundation donated $3 million to WSU’s Telitha E. Lindquist College of Arts & Humanities to provide training for arts specialists in Ogden and surrounding communities. The gift also provided funding for an endowed chair, Tamara Goldbogen, to oversee that training.

“It is an honor and a privilege to continue Beverley Taylor Sorenson’s great legacy of support for arts education in Utah,” said Goldbogen, who has watched the local program grow from two schools to 76 and reach approximately 36,000 students. “This growth would not be possible without the hard work and dedication of our arts specialists, administrators, classroom teachers, parents and community.”

Chapter 7

Chapter 7

In Memory of An Environmental Champion

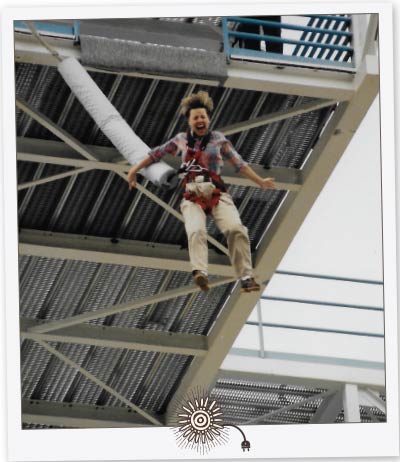

Elliot Hulet shows off a photo of his late wife, Susie Hulet, bungee jumping.

“She was small, but no one who ever spent any time with her would ever think of her as small,” Elliot said. “Her personality was so large, her stamp on our lives was so huge, that no one could ever think of her as little.”

“She was small, but no one who ever spent any time with her would ever think of her as small,” Elliot said. “Her personality was so large, her stamp on our lives was so huge, that no one could ever think of her as little.”

Standing 5 foot 2 inches, Susie loved outdoor adventures with Elliot and her friends. Early in their relationship, dates often took the form of backpacking trips. So, the couple’s support for environmental initiatives comes as no surprise.

“If you’re going to make the world better, you’ve got to make the environment better,” Elliot said.

Susie’s parents, the late John B. and Geraldine Goddard, established an endowment for WSU’s business school in 1998. After Susie passed away in October 2014, a legacy gift established the Elliot and Susie Hulet Scholarship for Sustainable Business to provide scholarships to WSU business students interested in sustainable business practices. The couple also formed the Elliot and Susie Hulet Conservation Study Awards, providing funds for WSU students to take part in Round River Conservation Studies’ conservation and environmental programs.

Last year, WSU launched the Susie Hulet Community Solar Program, offering the community discounts on solar energy. Susie also helped establish WSU’s Environmental Issues Committee and served on WSU’s Arts & Humanities Advisory Council (AHA!). Elliot currently serves on AHA! and recently made a gift to WSU’s National Undergraduate Literature Conference.

Last year, WSU launched the Susie Hulet Community Solar Program, offering the community discounts on solar energy. Susie also helped establish WSU’s Environmental Issues Committee and served on WSU’s Arts & Humanities Advisory Council (AHA!). Elliot currently serves on AHA! and recently made a gift to WSU’s National Undergraduate Literature Conference.

Before retiring, Elliot had a diverse career, including computer programming, web development and Transcendental Meditation. He was also an adjunct professor for the John B. Goddard School of Business & Economics. Susie held a long career in marketing with United Savings Bank and later dedicated her life to supporting charitable causes.

“That was her real gift,” Elliot said. “She connected people to causes.”

Chapter 8

Chapter 8

Using Supply to Ease Demand

It’s the holiday season in Utah, and it’s cold. Outside Catholic Community Services’ (CCS) Joyce Hansen Hall Food Bank on F Avenue in Ogden, clients are lining up and waiting hours, sometimes in the snow and rain, to be served. It’s hard for the food bank — the largest one in northern Utah, distributing more food than any other pantry in the state — to keep up with demand at this, its busiest, time of year.

Open from noon to 2 p.m. daily, clients line up at 9 a.m. and wait four to five hours to get inside. “So the question became, ‘How do we better meet their needs?’” said Marcie Valdez, who served as CCS Northern Utah director from 2009 to 2015. In spring 2015, the food bank had its answer, thanks to Weber State University supply chain management students.

Open from noon to 2 p.m. daily, clients line up at 9 a.m. and wait four to five hours to get inside. “So the question became, ‘How do we better meet their needs?’” said Marcie Valdez, who served as CCS Northern Utah director from 2009 to 2015. In spring 2015, the food bank had its answer, thanks to Weber State University supply chain management students.

For three semesters, students in assistant professor Sebastian Brockhaus’ courses worked with Catholic Community Services to identify ways to help improve the nonprofit’s processes, eventually recommending that the food bank open from 9 a.m. to noon daily, and one night a month. Clients now arrive at staggered times, reducing the amount of time it takes CCS to serve them.

“In supply chain management, the goal is to build an organization that can meet the needs of the customer at the lowest possible cost and avoid everything that doesn’t create customer value,” Brockhaus said. “We help organizations do the good things they already do better.”

Supply chain management students also helped the food bank improve the flow of shoppers through the pantry, eliminating delays and backups.

“I went to the food bank while people were shopping and timed how long it took at each station, to see which stations took the longest,” said Jacky Torres, a student who worked on the CCS project. “The goal was to identify the bottlenecks in the flow of shoppers. We also noticed shoppers having to turn around their shopping carts a lot because the walkways are narrow, making it hard for people to go through.”

Torres enjoyed her work with CCS. “I was able to do community service while applying what I was learning in class,” she said. “It helped me get a better idea of how the business world actually works.”

And that, of course, is the goal.

Chapter 9

Chapter 9

Dream 125: The Campaign for Weber State

Campaign Totals

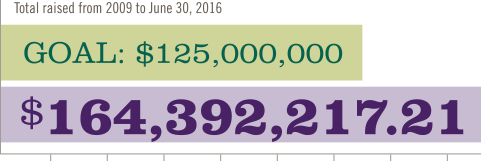

Total raised from 2009 to June 30, 2016

Goal: $125,000,000

Raised: $164,392,217.21

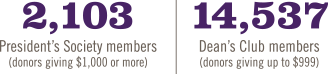

- 2,103 President’s Society members (donors giving $1,000 or more)

- 14,537 Dean’s Club members (donors giving up to $999)

- 16,640 alumni, friends and organizations have made campaign gifts

- 8,327 first-time donors

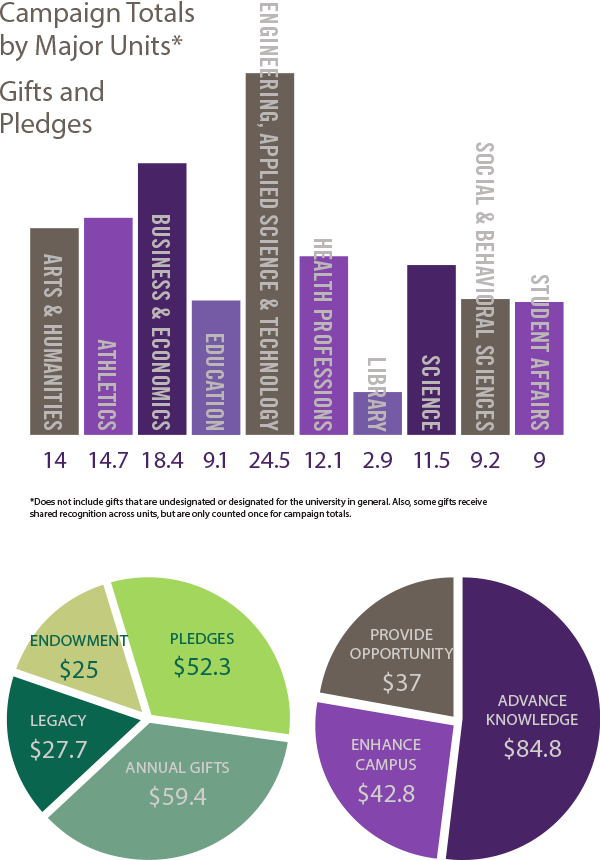

Campaign Totals by Major Units*

Gifts and Pledges (In Millions)

- Arts & Humanities: 14

- Athletics: 14.7

- Business & Economics: 18.4

- Education: 9.1

- Engineering, Applied Science & Technology: 24.5

- Health Professions: 12.1

- Library: 2.9

- Science: 11.5

- Social & Behavioral Sciences: 9.2

- Student Affairs: 9

*Does not include gifts that are undesignated or designated for the university in general. Also, some gifts receive shared recognition across units, but are only counted once for campaign totals.

- Annual gifts: $59.4

- Pledges: $52.3

- Legacy: $27.7

- Endowment: $25

- Advance Knowledge: $84.8

- Enhance Campus: $42.8

- Provide Opportunity: $37

Still curious about who sent WSU's mysterious $3 million gift?