Spring 1984, Volume 1

Article

William W. Lew

Journey to Minidoka: The Paintings of Roger Shimomura

William W. Lew, an Associate Professor and Curator in the Department of Art, obtained grants to bring the Roger Shimomura exhibit to Weber State College. He has also taught at universities in Ohio, Kansas, and Kentucky.

When I came back from church / heard the dream-like news that Japanese airplanes had bombed Hawaii. I was surprised beyond belief. I sat in front of the radio and listened to the news all day. It was said that this morning at 6:00 a.m. Japan declared war on the United States, Our future has become gloomy. / pray that God will stay with us.

-Toku Shimomura, December 7, 1941

Minidoka was located 30 miles east of Twin Falls, Idaho, in a one-time undeveloped federal reclamation project that has been described variously as God-forsaken and unfit for human habitation. Shortly after Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942, this obscure area in south-central Idaho secured a position in the annals of American history.

Executive Order 9066 displaced more than 110,000 persons of Japanese ancestry who were then residing on the West Coast, over 70,000 of which were American citizens. These persons were uprooted from their homes and incarcerated in ten camps situated in seven states across the United States, One of those camps was Minidoka. Roger Shimomura, then three years of age, was among the approximately 10,000 persons incarcerated in Minidoka. The artist recounts both the events which led to the incarceration and the camp experience in a series of paintings that has occupied him for the past several years.

The inspiration for these paintings is to be found in a number of diaries that recently came into Shimomura's possession. The diaries orginally belonged to the artist's grandmother, Toku Shimomura, who immigrated from Japan to the United States in 1912. From the time of her arrival until her death in 1968, Toku Shimomura faithfully chronicled her day-to-day experiences in this

country through her diaries.' Her personal accounts of events that profoundly affected the Japanese American community during World War II serve as the basis for this recent series of paintings.

To enhance the ethnic impact of the paintings and the subject matter contained within, Shimomura transcribes and interprets the passages from his grandmother's diaries in the styles of the 18th and 19th century Ukiyo-e artistic traditions of Japan. A female figure in a colorful kimono calls to mind an Utamaro courtesan, a snow-capped mountain or a vermilion torii suggest the woodcut prints of Hokusai and Hiroshige. These Ukiyo-e elements are often found in unlikely juxtapositions with objects drawn from 20th century popular culture such as an "art deco" radio, the silhouette of Superman, the partially hidden figure of a Santa Claus, an angel food cake, or levolor blinds. As disparate and anachronistic as these juxtapositions might appear, they point to an interest that has been manifested in Shimomura's paintings since the early seventies-an artistic sensibility that is uniquely and distinctly Japanese American in character.

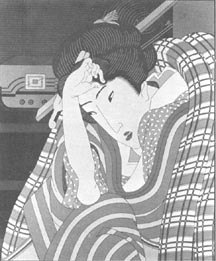

An example of this juxtaposition is to be found in the work entitled December 7, 1941 (Pearl Harbor Day), which appropriately serves as a symbolic and thematic frontispiece for this series of paintings (figure 1),2 The diary entry that inspired this particular work also serves as the introduction to this article. Here the artist presents us with a stylized portrait of Toku Shimomura. She is shown wearing an elaborate hairdo and wrapped in a heavy Japanese blanket called a futon. Behind Toku and to her left is to be seen the radio that broadcasts the news of the dawn attack on Pearl Harbor. In contrast to the Ukiyo-e style in which the artist's grandmother is rendered, the radio reflects an "art deco" style that is befitting of the 1930's and 40's. With her hand touching her forehead, Toku listens intently to those events that subsequently would affect not only her life, but that of her grandson, and the entire Japanese American community on the West Coast.

The anti-Japanese hysteria that gripped this country in the aftermath of Pearl Harbor is thoroughly documented in numerous sources. The Issei (first generation immigrants from Japan) who were aliens prior to the attack on Pearl Harbor had suddenly become enemy aliens. Responses to this new status accorded the Issei varied greatly within the various departments of the federal government.

Fig. 1

December 7, 1941 Pearl Harbor Day

When I came back from church I heard the dream-like news that Japanese airplanes had bombed Hawaii. I was surprised beyond belief. I sat in front of the radio and listened to the news all day. It was said that this morning at 6:00 a.m. Japan declared war on the United States. Our future has become gloomy. I pray that God will stay with us.

The Department of Justice's position, as expressed by U.S. Attorney General Francis G. Biddle, was that the Bill of Rights protected not only American citizens but all individuals who lived within the jurisdiction of the United States. The civil rights of an enemy alien were also to be respected provided there was no cause to doubt that alien's loyalty to this country. An opposing position was held by Lieutenant General John L. DeWitt, Commanding General of the Western Defense Command. He viewed the Issei more as an alien who was an enemy of this country than as an alien who had emigrated from a country that was now at war with the United States. Under the auspices of military security, DeWitt proposed, among other matters, that enemy aliens be prohibited from strategic areas of the West Coast. As history reveals, it was this latter view that was to prevail and that eventually was to lead to the mass evacuation and incarceration of both Japanese immigrants and Japanese Americans residing on the West Coast.

Fig. 2

February 3, 1942

When I finally decided to do my fingerprint registration since it had been hanging heavily on my mind. I went to the Post Office with Mrs. Sasaki. We finished the strict registration at 11:00 a.m. I feel that a heavy load has been taken off my mind.

As part of the defense program, Congress passed an Alien Registration Act in 1940. This Act required all aliens over the age of fourteen to be registered and fingerprinted. Efforts to identify enemy aliens, especially those of Japanese ancestry, were intensified after the attack on Pearl Harbor. In a meeting which took place in San Francisco on January 4, 1942, between DeWitt and representatives of the Justice and War Departments, a new plan was proposed to register enemy aliens a second time. The painting entitled February 3, 1942, alludes to the process of re-registration to which the Issei and other so-called enemy aliens were subjected (figure 2). In her diary, Toku Shimomura recounts how she and her friend journeyed to the post office to be fingerprinted and the sense of relief that followed after having taken care of a matter that "had been hanging heavily on my mind." In this painting the artist depicts his grandmother and her friend in conversation, presumably at the post office where the two had been fingerprinted. Traces of the ink are still to be seen on Toku's fingers. As in the previously discussed painting, the two figures are rendered in the Ukiyo-e style with much attention given to the kimonos and the elaborately arranged hairdos. They are viewed from afar through open windows. Like the "art deco" radio, the architectural elements which frame and confine the two figures provide a counterpoint to the Ukiyo-e style. Additionally, the architectural elements subtly restate and reinforce the subject matter of the painting on a symbolic level. As one studies the grain of the paneled wood walls, one begins to realize that it is, in fact, composed of large fingerprint images.

On February 19, 1942, sixteen days after Toku and her friend were fingerprinted, Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066. This Executive Order gave Roosevelt's Secretary of War and his subordinates the authority to designate certain areas in the United States as military areas and, under the auspices of military necessity, to remove certain peoples from those areas. On February 20, the Secretary of War appointed the previously mentioned DeWitt to carry out the terms of this Executive Order. On March 2, DeWitt issued Proclamation No. 1, which identified and divided the states of Arizona, California, Oregon, and Washington into military zones. On March 11, DeWitt established the Wartime Civil Control Administration (WCCA) to carry out the evacuation of all persons of Japanese ancestry from military zone *1. This zone included the southern onethird of Arizona and the western halves of the three Pacific Coast states. On March 18, Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9102. This Executive Order established the War Relocation Authority (WRA), which was to assist the military in the evacuation process and to oversee the camps. Four days after the signing of this Executive Order the first large contingent of persons of Japanese ancestry was removed from their homes and incarcerated.

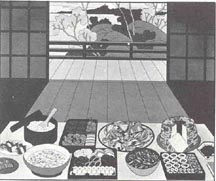

The evacuation process consisted of two phases: in the first phase the evacuees were moved into temporary assembly centers that were manned by the WCCA; and in the second phase the evacuees were transferred to more permanent relocation centers that were situated in the interior and manned by the WRA. Those evacuees from the Seattle area enroute to Minidoka were first detained at the temporary assembly center located on the Puyallup Fairgrounds in Puyallup, Washington. On the eve of their evacuation to this temporary assembly center in Puyallup, Toku and her family had one last farewell dinner in Seattle. The artist makes reference to this last supper in his painting entitled April 26, 1942 (figure 3).

In the diary entry that inspired this painting, Toku recounts the events of the day, beginning with a physical examination at the doctor's office, followed by a meeting at the church where she bade farewell to her friends.3 Finally, the Shimomura family gathered together for one final meal before the morning's sojourn to the temporary assembly center. In this last supper scene the artist provides us with a glimpse of a typical Japanese American meal. On the table is to be found a number of lacquer trays and bowls which contain such Japanese dishes as steamed rice, makisushi, inarisushi, and pickled vegetables. These food items are shown together with such American favorites as fried chicken and angel food cake. To the lower right corner of the painting, partially cropped by the painting's edge, is to be seen the diary which records this event. The diary, in fact, is an unobtrusive and almost hidden element in the majority of the paintings which make up this series of works.

Fig. 3

April 26, 1942

At 8:00 a.m. all of the family went to the doctor's for a physical examination. At 11:00 a.m. we went to church for a last gathering. We regretted to say farewell. We all cried. I pray from my heart that the earliest possible peace would come and all of us would be able to meet here again. All of our family, including Yoichi (son-in-law) and Fumi (daughter) had a last farewell dinner with chicken. It touched me deeply in the heart.

The meal is set before an open entranceway which provides a view of a landscape with blooming trees in the foreground and a snow-capped mountain in the distant ground. A double-entendre image, this landscape scene can be interpreted as either a reference to Hokusai's many woodcut prints of Mount Fuji or to Mount Ranier, one of the scenic landmarks that can be seen to the south of Seattle on clear days. This tranquil landscape scene is interrupted by a foreboding railing that cuts across the open entrance and that perhaps foreshadows the internment that is to take place on the following morning.

The meal that is shown in this painting is in sharp contrast to one which Toku hesitantly eats while confined in the temporary assembly center in Puyallup. Throughout the diary entries which serve as the source of inspiration for this series of paintings, Toku reveals a calm reserve and an acceptance of the events that have befallen her, her family, and the Japanese American community of Seattle. Some semblance of a complaint, however, is to be sensed in the entry dated May 21, 1942. In this entry, Toku makes reference to a diet of wieners and bologna that has left her with a poor appetite. In the painting entitled May 21, 1942 the artist shows his grandmother holding a bowl of rice and wieners (figure 4). A slight grimace is to be detected on Toku's face as she turns her head away from the food. From a sociological rather than a biographical or personal viewpoint, the differences reflected in the two food paintings and in Toku's response to the food that is before her in the latter painting imply much more than a change in diet. In one sense, the community mess halls, both in the temporary assembly centers and the more permanent relocation camps, did much to undermine the traditional family structure. The effects of mess hall conditions in the centers are noted by Harry H. L. Kitano in his Japanese Americans: The Evolution of a Subculture. Professor Kitano makes the following observations:

Fig. 4

May 21, 1942

Early in the morning the laundry area looked like a battlefield. I started to eat my meals in my room. The lunch meal was wieners and once again at dinner it was bologna. I had a poor appetite. I spent time cleaning and doing laundry. Yoichi Hayakawa put our name on our bucket and washtub. At night I could not sleep so I took a pill.

In general, under the influence of mess hall conditions, eating ceased to be a family affair. Mothers and small children usually ate together, but the father often ate at separate tables with other men, and older children joined peers of their own age. Thus family control and the basic discipline of comportment while eating changed character rapidly, and different family standards became merged into a sort of common mess hall behavior. Family groups ceased to encourage the enforcement of customary family rituals associated with the mealtime gathering of the group. The social control exerted by the family under more normal circumstances seemed to be loosening.4

From this broader context, Toku's actions can be interpreted as a response not only to unfamiliar and undesirable food, but to a situation that ultimately would hasten the erosion of cultural traditions and values held dear by the Issei.

Toku's response is reinforced on a symbolic level by the landscape scene that is to be seen through the window behind her. A study of sharp contrasts is to be noted when comparing this landscape to that found in the previously discussed last supper painting. The lush spring landscape of the last supper painting gives way in the latter to a scene that is barren and devoid of vegetation, even though this event takes place in the month of May. Also, the bright late afternoon light gives way to twilight darkness. Furthermore, the pronounced railing of the last supper painting is here transformed into a barbed wire fence.'

In these two paintings, the artist uses the landscape-its transformation-to illustrate the plight of the Issei and the concern for their cultural traditions and values. More likely than not, the process of acculturation eventually would have transformed the Issei way of life. The process, however, would have been gradual and less traumatic had not the camp experience interceded. If life in camp did not hasten the acculturation process tremendously, it certainly did do much to undermine those traditions and values.

By late May, 1942, the majority of the more than 110,000 persons of Japanese ancestry residing on the West Coast had been evacuated from military zone 01. By June 5, the evacuation of military zone *1 was completed, and both Japanese immigrants and Japanese Americans were detained in the temporary assembly centers. According to numerous accounts, and in contrast to Army reports, conditions in the temporary assembly centers were far from ideal. In fact, it is surprising that so few epidemic outbreaks resulted from the unsanitary conditions in some of these makeshift facilities. Mine Okubo, a Japanese American artist who also documented the incarceration process in her art, provides the following description of her living quarters at the Tanforan Assembly Center in California:

The roof sloped down from a height of twelve feet in the rear room to seven feet in the front room; below the rafters an open space extended the full length of the stable. The rear room had housed the horse and the front room the fodder. Both rooms showed signs of a hurried whitewashing. Spider webs, horse hair, and hay had been whitewashed with the walls. Huge spikes and nails stuck out all over the walls. A two-inch layer of dust covered the floor, but on removing it we discovered that linoleum the color of redwood had been placed over the rough manure-covered boards.6

The Puyallup Assembly Center, where Toku was detained, had been and still is a fairground. Like the living quarters at Tanforan, a facility in the fairground that was used to exhibit and house livestock had been hastily converted for human habitation. Toku and the Shimomura family lived in the temporary quarters of the Puyallup center for some three months before they were transferred to Minidoka.

One of the major reasons for the two phase evacuation process was to allow time for the construction of the more permanent inland relocation centers, The Minidoka Relocation Center in Idaho received its first group of evacuees from the Puyallup Assembly Center on August 10, 1942. Toku and the Shimomura family arrived shortly thereafter.

Life in the more permanent inland relocation centers, as described by Roger Daniels in his Concentration Camps USA: Japanese Americans and World War II, was generally not brutal. Rather than an Auschwitz or a Vorkuta, Professor Daniels likens these relocation centers to our Indian reservations.7 Nevertheless, these centers were still places of confinement, made so by the barbed wire fences that surrounded them, by the armed sentries that patrolled them, by their isolated geographic location, and ultimately by the strong anti-Japanese sentiment that was then prevalent in the United States. The barbed wire fence makes its first appearance in this series of paintings with the landscape of May 21, 1942. A symbol of confinement, it also appears in several other paintings from this series. One such painting entitled September 2, 1942, interprets a diary entry that was written several weeks after Toku's arrival at Minidoka (figure 5). Even during such a time of duress, Toku is able to maintain peace of mind, if only for short and intermittent periods. Of that day Toku recounts, "The morning air was fresh. I woke up early to experience the peacefulness for a few moments," This, perhaps, is the most unusual painting of the series. The artist presents us with a landscape painting the composition of which is reminiscent of one found in a Japanese album leaf or fan painting. In the foreground and enveloping two-thirds of the painting's surface is to be seen a profusion of wild and colorful flowers, In the middle ground is to be seen a hawk that is perched on the barbed wire fence. Beyond the barbed wire fence is a broad and desolate expanse of land.

Fig. 5

September 2, 1942

The morning air was fresh. I woke up early to experience the peacefulness for a few moments.

Once again, symbolic landscape depiction plays a role in this series of paintings. The barbed wire fence, a symbol of confinement, defines the perimeter of the camp. The hawk, a symbol of freedom, straddles the barbed wire and is at liberty to fly on either side of the perimeter. The dense vegetation and foliage of the near side of the perimeter is in sharp contrast to the barrenness of the landscape on the far side. A certain ambiguity exists as to whether the foreground landscape or the distant ground represents the confined camp area. Because of the vastness of the land to be seen in the distant ground, one would assume that the foreground area represents the confines of the camp. If so, then perhaps the lush vegetation and flowers might well symbolize a mental attitude rather than physical freedom. Shimomura concludes the year of 1942 on a positive note with a painting of a Christmas celebration entitled December 25, 1942 (figure 6). In this painting a Santa Claus is shown entering a room. He is partially obscured by a gridded screen which, with the exception of the entranceway, runs the length of the painting. The figures participating in this Christmas celebration are silhouetted against this screen. Of that Christmas day Toku notes:

The muddy ground was completely covered by snow. It was like a beautiful white cloth and a suitable sight for Christmas. The dinner was in mess hall number 7. The waitress' (sic) and cooks were all dressed up in the beautifully decorated mess hall. The radio emitted melodies of Christmas. We happily sat at our family table. At 9 p.m. Santa Claus appeared. For these moments I forgot where I was.

Toku and the Shimomura family were to remain incarcerated in Minidoka for more than a year and a half after this date. Yet, even under the extenuating circumstances of World War II, Toku managed to see the positive side of her situation and to maintain an air of optimism throughout most of her ordeal. The festive mood of this Christmas celebration is in sharp contrast to the mood of the event that initiated the incarceration process a year earlier on December 7, 1941. The radio, which brought news of the bombing of Pearl Harbor and Japan's declaration of war against the United States on that fateful day, now fills the mess hall with the glad tidings of Christmas.

This series of paintings by Roger Shimomura allows for interpretation on two distinct but interrelated levels. On one level the series provides a visual biography which illuminates the personal experiences of a Japanese immigrant as she adapts to life in the United States during a tragic period of global conflict. On a broader and more universal level of interpretation the series makes reference to the human condition of a subculture struggling to survive in the United States. In its totality, this series of paintings places Toku's personal experiences within the larger social, political, and historical context of the Japanese American experience; Toku, in fact, personifies the Japanese American experience during the trying times of World War If. As portrayed by her grandson, Toku is a dignified figure who reveals an optimistic attitude about life. It is this optimism that carries her through this period of great duress. To preserve and enhance the ethnic character of his viewpoint, Shimomura deliberately chooses to interpret the events in the guise of the 18th and 19th century artistic traditions of Japan.

Fig. 6

December 25, 1942

The muddy ground was completely covered by snow. It was like a beautiful white cloth and a suitable sight for Christmas. The dinner was in mess hall number 7. The waitress' [sic) and cooks were all dressed up in the beautifully decorated mess hall. The radio emitted melodies of Christmas. We happily sat at our family table. At 9:00 p.m. Santa Claus appeared. For these moments I forgot where I was.

Notes

1 ToKu Shimomura recorded the events of her life in Japanese. Roger Shimomura, who is a Professor of Art at the University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas, received research grants from that institution in 1981 and 82 to have the diaries translated into English. The diary entries referred to in this paper are quoted from those translations.

2 The artist has since painted two additional versions of this work, each with a different composition. Mention should also be made that the painting entitled April 26, 1942 (discussed later), also exists in a second version, the composition of which varies greatly from the first.

3 According to the artist, Toku was a very religious person, "a Methodist before she immigrated to the day she died." Toku's passive and somewhat stoic response to the events that had befallen her and her family were perhaps the result both of her strong belief in her religion and of her display of a cultural trait that is often described by the Japanese term gamman, which loosely translated means "to hold it in."

4 Harry H. L. Kitano, Japanese Americans: The Evolution of a Subculture (New Jersey: Prentice Hall, Inc., 1969), p. 37.

5 The use of symbolic landscape depictions to enhance the content of a painting finds precedent in both Western and Far Eastern traditions of painting. One of the finest examples of this kind of landscape treatment in Renaissance art is to be found in Piero della Francesca's Resurrection of circa 1450. In this painting the resurrected Christ serves as a vertical axis for the composition, bisecting the landscape behind Him into two halves. To the left of the Christ figure is seen a desolate landscape with leafless trees; to the right of Him are trees that are in full bloom and covered with foliage. in Piero della Francesca's painting, the rebirth of nature corresponds to and parallels the resurrection of Christ. This convention of symbolic landscape depiction is to be seen in an entirely different context in a Chinese painting entitled The Parting of Su Wu and Li Ling, attributed to a 10th century artist named Chou Wen-chu. This painting recounts a well-known episode in the Han dynasty of Chinese history. Su Wu and Li Ling were two famous Chinese generals of the Han dynasty. During a turbulent period in the Han dynasty, each general pursued a different course of action; Su Wu remained ever loyal to the Han dynasty while Li Ling betrayed it by surrendering himself to the barbarians. The scene in the painting depicts the tearful farewell parting of these two comrades. The rich and fertile background landscape around Su Wu is a testament to and glorification of his loyalty to the Han, whereas the barrenness of the landscape near Li Ling points to his betrayal. A more thorough discussion of the symbolic aspects of the landscape in this painting is to be found in Chu-tsing Li, The Freer "Sheep and Goat" and Chao Meng-fu's Horse Paintings (Ascona, Switzerland: Artibus Asiae Publishers, 1965), pp.36 - 41.

6 Mine Okubo, Citizen 13660 (New York: Arno Press, 1978), p. 35.

7 Roger Daniels, Concentration Camps USA: Japanese Americans and World War II (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, Inc., 197 1), p. 105.